The following is partly an abstract from the article below, which is far more detailed, but in Dutch.

Max was born on July 22, 1914, in Kendangang South-East Borneo. His parents, Theo Horstink and Louise Horstink-Tichelaar, lived there because of the position of his father who was stationed there as Captain KNIL (Netherlands East Indies – NEI – Army) at the Topographical Service. Max’ father was a well-known topographer and lecturer at the University of Bandung.

After high school he went to the Royal Military Academy (KMA) in Breda, Netherlands where he graduated as an army officer. He married in the Netherlands and in 1936 traveled back to NEI with his wife Greet Max, to start his career. Here he did his pilot training, but because of uncertain circumstances he switched career and was assigned to the Topographical Service. Shortly after he finished this training, in December 1941 the VIII Battalion Infantry in Malang became his mobilisation destination, and a week later part of this battalion was placed with the Dilli expeditionary force for Timor. Together with Australian troops (Sparrow Force), the KNIL would occupy and guard Timor as the island was an important “steppingstone” between Australia and the NEI.

After close to a year of guerilla fighting – known as the Battle of Timor – the Australian and Dutch forces were evacuated to Australia. While they had been unable to stop the Japanese onslaught, they had been instrumental in delaying the Japanese advances further into the Southwest Pacific.

After a training at Archerfield Airport in Brisbane, Max was back in the air force, and placed at the 18 NEI Squadron RAAF in McDonald airfield near Darwin. This time not as a pilot but an observer and bombardier (bomb aimer). His first mission in April 1943, turned out to be more of a reconnaissance flight as no bombs were dropped. On this flight Gus Winckel was the pilot. Many more bombing raids followed this first mission. In all he flew 34 missions.

Again for unknown reasons in September that year he was placed at the NEI intelligence service (NEFIS) in Melbourne, from here he moved on, in June 1944, to the Netherlands Indies Civil Administration (NICA) and was promoted to captain. NICA oversaw the re-establishing of Dutch administration in the liberated parts of NEI. He started his new job as a Commanding Officer NICA (CONICA) in Dutch New Guinea in late 1944. He also saw the evacuation of Sargent Mauritz Kokkelink and his guerilla fighters. Kokkelink is one of the highest decorated NEI military, his group has kept fighting for more than 2 years in Dutch New Guinea.

Next, we find Max in Borneo in May 1945. Here he was part of Operation Platypus VIII, of the Allied Services Reconnaissance Department (SOE Australia), a series of reconnaissance and missions behind Japanese lines with the aim of obtaining intelligence on Japanese strength in Borneo and fueling the resistance. Their activities ended when Japan surrendered in August that year.

Max was now put in charge of setting up one of the Army Organisation Centre (Leger Organisatie Centra – LOC) in Bandung. These Centres, together with the RAPWI organisation (Recovery of Allied Prisoners of War and Internees) were charged with tracing, supporting, and transporting prisoners of war and internees.

The situation immediately after was ended was chaotic. Indonesia declared its independence; the Allied Forces had put Japanese in charge of guarding the camps where European women and children and in other camps POWS were interned, as fanatic Indonesians started to look for Europeans with, in many cases, the aim to kill them. The Netherlands had not yet been able to send troops to Indonesia to restore the security. British militaries were sent to Java to take control over from the Japanese, but they of course could not be everywhere quick enough to suppress the violent uprising (Bersiap).

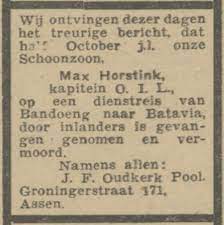

Reconstruction of what follows looks like that Max and others went from Bandung to Bavaria for a meeting. Some people decided not to go back to Bandung and Max and 10 others decided not to travel by plan but instead travelled in two cars to Bandung. They had to travel through areas controlled by the Indonesians, most likely they thought that, if needed, they would be able to fight their way to Bandung. Whatever the situation, they were captured at Tjiandjoer and hacked to death.

In December 1945, Tjiandjoer was occupied by a British Gurkha regiment, and they became aware of what had happened there in October. The mutilated bodies were recovered and identified. It was not until 19 June 1948 that several of them, including Max Horstink were buried at the Pandu war cemetery in Bandung.

The information in the document below is in Dutch.

The DACC received the following email from Ed Wills in relation to the article above.

| Congratulations on your web site that I make use of in my research on WWII in East Timor. I refer to the interesting and comprehensive biographical article on Max Horstink. Wherein it is stated on p. 8 of the linked file: Evacuation to Australia By the end of 1942, the situation of the Allied forces in Timor had become so weak and the island’s importance too small in General MacArthur’s plans that the decision was made to evacuate the troops. On the night of 10 to 11 December 1942, Max and seven other officers and about 190 KNIL soldiers and part of the 2/2 Ind. Coy with the Dutch destroyer Hr. Ms. Tjerk Hiddes transferred to Darwin. However, the information conveyed in the second paragraph is inaccurate. In support of this assertion, please see the following extract from: Jack M. Ford. – ‘Allies in a bind’: Australia and the Netherlands East Indies in the Second World War. – Loganholme, Qld.: Australian Netherlands Ex-Servicemen and Women’s Association, Queensland Branch, [1996]: 162-163. This book is promoted in another article on your website: ‘Allies in a Bind – Australia and the Netherlands East Indies in the Second World War’ Published by DACC on February 20, 2022 — https://dacc.net.au/archive/dutch-australian-history/military-political-history/allies-in-bind-australia-and-the-netherlands-east-indies-in-the-second-world-war/ The evacuation of the Sparrow Force survivors on 12 December did not end the KNIL presence on Timor. Left behind with the 2/4th Independent Company were Horstink and 15 KNIL volunteers. As Callinan had also remained on Timor to command a reduced Lancer Force then it is probable that he specifically asked for Horstink to remain behind, as the Australian commander thought highly of that particular KNIL officer. Horstink’s unit comprised six sergeants, two corporals and seven privates. [69] On 19 December, only five days after the evacuation of the main KNIL force, Horstink had requested further stores for his men and whatever Portuguese Timorese auxiliaries they could arm. He wanted 2000 rounds of Johnson rifle ammunition, 4000 rounds for the Mannlicher rifles, 6000 rounds for the Lewis Guns and 1000 rounds of pistol ammunition as well as a radio and 30 electric torches. [70] The Tjerk Hiddes had delivered some supplies to Betano Bay on 17 December but Horstink was not to get his requested supplies, as MacArthur decided to evacuate the remainder of Lancer Force from Timor. Increasing Japanese pressure on the guerrillas and the destruction of pro-Allied villages, meant that by the beginning of 1943, Lancer Force’s position had become untenable. On 10 January 1943, the 2/4th Independent Company and Horstink’s men were evacuated from Timor by the destroyer Arunta. After Horstink’s evacuation, there remained some minor administrative issues to be resolved. Thus there was the mundane task of sorting out the KNIL supplies that had reached Darwin too late to be sent to Timor. This was left in Bakkear’s hands. On 14 February 1943, Bakkear found that he held the following KNIL stores: seven boxes of ammonal explosive, 143 boxes of wet slabs of gun cotton, 41 boxes of dry primers of gun cotton, 4 cases of gelignite, 16 land mines, 72 mortar shells, 12 packing crates for mortar shells, 2660 rounds of pistol ammunition, five hurricane lamps, 29 hand towels, one case of webbing, four cleaning rods, one colt pistol, one case of rations, 20 gallons of kerosene, two gallons of methylated spirits and 15 mosquito nets. [71] So Bakkear offered them to the Australian Army’s ‘Z’ Force commando unit, 51st and 81st Field Armaments Depots at Darwin, with payment to be arranged through the NEI Commission. From January 1943 until the end of the War, only small numbers of operatives belonging to NEFIS and AIB were sent back to Dutch Timor. For the Dutch, the Timor guerrilla campaign from February 1942 through to January 1943 had brought both benefits and disaster to their weakest military arm, the KNIL. On the negative side, Snell and 60 other fresh KNIL soldiers were lost in the Armidale sinking thus effectively destroying one of the two KNIL platoons that had been reformed in Australia. On the positive side, the Dutch were able to evacuate a total of 217 battle-experienced soldiers from the island. Apart from Van Straaten in May 1942, Breemour’s men in December and Horstink’s men in January 1943, another eight KNIL soldiers had been evacuated from Timor, during the period 26 June to 9 October 1942. They were Lieutenants Begeman and Schreuder and Privates Auta, Anchutsz, Capellen, Elink Schuurman, Hiskemuller and Margus, who were evacuated due to illness. [72] The KNIL benefited from the jungle training gained from their ten month guerrilla campaign. As well, the Australians and the KNIL learnt to co-operate successfully together in a combat command and this was to be of value in the future. The Dutch went even further, as they saw the significance of the Timor Campaign in terms of future post War co-operation between the two Allied nations. REFERENCES [67] AWM File, Series AWM 54, Item 571/4/28, Lancer Force (Dutch Troops) on Timor, ‘Dutch Troops Evacuated’ list, 2 January 1943. [68] Ibid., Captain De Vries, report to Coster, 14 January 1943. [69] Ibid., Sparrow Force, signal to Norforce, 19 December 1942. [70] Ibid. [71] AWM File, Series AWM 54, Item 571/4/28, Lancer Force (Dutch Troops) on Timor, Acting Quarter-Master General, NT Force, letter to Bakkear, 14 February 1943. [72] Ibid., Norforce, list of NEI Troop Evacuees from Timor from 26 June to 9 October 1942. You may wish to revise the Horstink article in the light of the information conveyed by Ford. Kind regards Ed Willis Committee member, 2/2 Commando Association of Australia https://doublereds.org.au Sent from Dutch Australian Cultural Center |