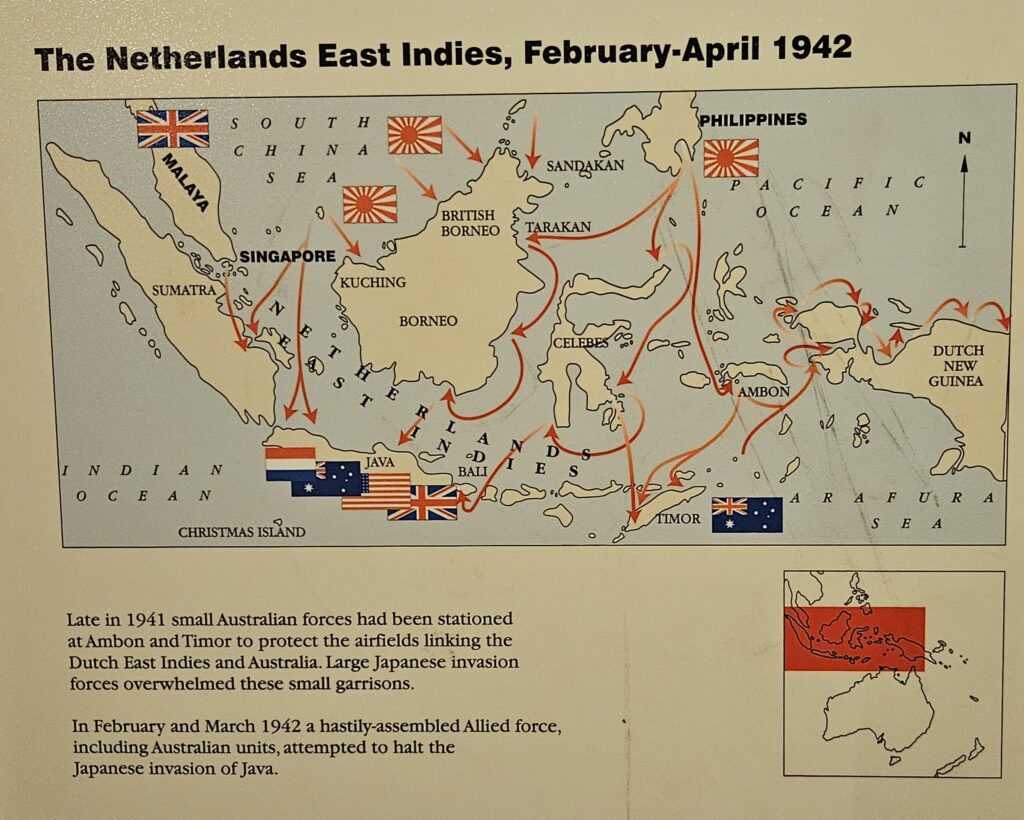

Allied Forces in Java at the time of the Japanese invasion

| East Java KNIL: VIth Regiment, IInd & IIIrd Landstorm Battalions, artillery battalion, Marine Battalion (motorised); US: 131st Artillery Regiment’s ‘E’ Battery Central Java KNIL: XXIst Battalion, 2 cavalry squadrons, armoured car squadron, British: 79th Heavy AA Regiment; West Java KNIL: Ist, IInd & IVth Regiments, Ist Artillery Regiment, Landstorm battalion, mountain artillery battalion, cavalry company, ‘Mobile Force’; US: 131st Artillery Regiment’s 2nd Battalion; British: 3rd Hussars Regiment ‘s ‘B’ Squadron, 21st Light AA Regiment, 48th Light AA Regiment, 6th Heavy AA & 35th Light AA Regiments, RAF composite airfield defence company; AIF ‘Blackforce’: 2/3rd Machine-Gun & 2/2nd Pioneer Battalions, 2/6th Field & 105th General Transport & 2/3rd Motor Reserve Companies, company HQ, Guard Battalion platoon & 265 unattached troops; |

Source Allies in a Bind

Dutch and Australian troops largely on their own

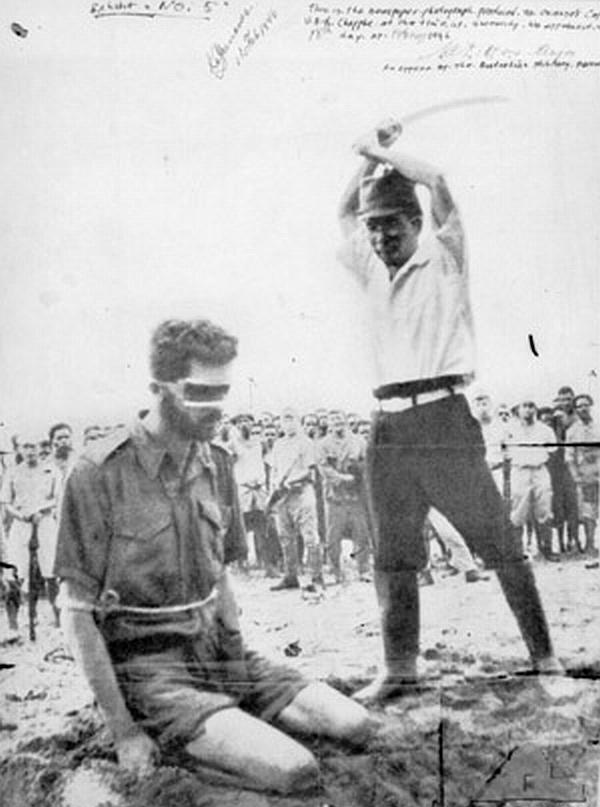

After the heavy losses during the Battle of the Java Sea the British and American forced started to withdraw and the Dutch and Australians were largely left on their own. ABDA Force Commander British General Sir Archibald Wavell basically dissolved ABDA (American, British, Dutch, Australian Force) and left for Ceylon on February 25. Several totally under resourced units kept fighting till the bitter end, supported by what ever was left of the Netherlands East Indies (NEI) air and naval forces. On a few occasions they were able to incur significant losses on the side of the Japanese, who retaliated by killing all Dutch and Australian POWs and often also the civilians who had supported them.

While there were such heroic events at the same time the Australians rightly bitterly complained about the KNIL. The NEI Army mostly consisted of local voluntary militias units with little or no training, there was a shortage of guns, ammunition and vehicles, let alone more serious material. Communication was often non existence and local post offices had to be used to rely messages. This also stopped functioning when the national telecoms infrastructure was bombed out of order by the Japanese.

On March 1, the American P-40 were evacuated from Djokjakarta to Australia. Three of the P-40 came immediately under fire and were lost. The Dutch P-40s were not allowed to evacuate and instead were ordered to stay in NEI. The Australian base of the RAAF Squadron at Kalidjati was totally unexpectedly conquered by the Japanese within a day of their landing on the north coast of Java, the four Hudson were able to flee while the Japanese opened fire on them. The last American (overloaded) B-24 bomber left Djokjakarta the following day with 35 ground staff.

For most far too late a more official evacuation was now launched by the Dutch, against the will of the Dutch Government in London. KNILM planes were used to evacuate the ‘lucky’ ones. Finally on 7 March the last plane left with the Lieutenant Huibert van Mook and several other officials, who would start what would become the Netherlands East Indies Government in Australia.

On Sunday, 8 March, Lt. Gen. Hitoshi Imamura met with the Governor-General of the NEI, Jonkheer (Lord) Alidius Tjarda van Starkenborgh Stachouwer and set a deadline for an unconditional surrender. However, some days before this event he had hand-over the military authority to Lieutenant General Hein ter Poorten . It was Ter Poorten who was ordered by the Japanese to sign the capitulation. They officially surrendered at 1:00 p.m on the 9th of March. Because poor communications some small units did fight on for a few more days, a few disappeared in the jungle and stayed there for years.

However the Governor-General was not a part of the surrender. Also days before he had handed over all civil authorities to Hubertus van Mook with the order to establish a Government-pin-Exile in Australia. Technically therefor the Japanese had never official control over the civil affairs of NEI.

Both Governor General and Tre Poorten and their families ended up in the notorious Japanese camps. See also: Boek: Van Starkenborgh (1888-1978) De laatste gouverneur-generaal van Nederlands-Indië.

There are relative few pictures of the Japanese invasion into NEI. These are from the book: Het Koninklijke Koloniale Nederlands-Indische Leger 1830-1950.

Making up the balance

Dr. Jack Ford made up the balance in his book Allies in bind: Australia and the Netherlands East Indies relations during World War Two.

The loss of the NEI was a disaster for the Dutch, greater than the loss of Malaya to Britain, or the Philippines to the USA. Only northern Sumatra, the Arafura Sea Islands, DNG and the Dutch West Indies remained under Dutch control. The Dutch fought a series of battles for three months with minimal British and US support. Britain lost 10 warships, a light tank squadron, five AA regiments and about 100 aircraft. The US lost 12 warships, an artillery battalion and about 140 aircraft. Most of their naval losses occurred evacuating not defending the NEI. Having smaller resources, Australia lost 5 battalions plus support units, about 40 aircraft including 3 QANTAS flying boats, Perth and Yarra. Left behind were 1,075 Australian prisoners of war on Ambon, 1,137 POWs on Timor and 2,736 POWs on Java. Their uncertain fate left some Australians bitter towards the Dutch throughout the war. The Dutch bore the brunt of the fighting. Their losses were irreplaceable, being most of their navy (87 warships), nearly all their 300 planes and the entire KNIL (121,000 troops). For the Dutch, who lost everything, only Australia put in a strong effort to support the NEI whereas US and British losses were comparatively low.

Japanese losses of 11 warships, 20 merchant vessels, 8 small ships and 20+ motorized barges were greater than in the Philippines or Malayan Campaigns. Japanese air losses were similar in the NEI and Malayan Campaigns (120 and 171 aircraft destroyed respectively). Japanese army losses were light (255 soldiers) compared to losses of 3,833 soldiers in Malaya, but the Japanese army only fought on Java. Marines were used in most invasions. Paratroop losses were heavy. Japan had a single paratroop battalion, dropped at Menado, Palembang and then Timor. While transport losses were few (about 6 planes), at least half of the battalion became casualties in the three operations. Only 78 paratroops survived the Timor operation, while at Palembang they suffered a 25% casualty rate on the first day. The paratroops would not be employed again until 26 November 1944.

It is also important to note that the Dutch did not command the major battles that in the end resulted in the loss of NEI, These were ABDA battles under the control of the British General Wavell.

Jack continues this story in his book as follows:

The Japanese who won the NEI Campaign can have the last word on the Allied defeat. Japanese invasion force commander General Imamura stated that:

The greatest mistake of the Dutch Government …concerning the defence of the East Indies seemed to be that it transferred supreme command in the Dutch East Indies from the Governor-General to General Wavell of Britain, who commanded only 10,000 British and Australian forces altogether. In fact, General Wavell fled to India by air when the Japanese troops began to land and move forward in East and West Java, leaving the Allied forces behind. As a result, the remaining Allied forces did not follow the lead of Commander ter Poorten at all, making it very difficult for him to carry out his strategy. I think it was natural that the commander lost the will to fight. Had the Allied forces in Java been commanded by the Governor-General, the Japanese army would have had to face a tough battle.

Newspaper article below how much the war situation can change within two weeks

Prewar assessments of the KNIL by Australian military officers

Before the outbreak of the Pacific War, Australian military observers had already formed a critical view of the preparedness of the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army (KNIL). In November 1941, Major J. H. Brown of the Australian Army visited Java and reported serious shortcomings in KNIL training and command during field exercises. His observations, later supported by the Australian Directorate of Military Intelligence, concluded that while the KNIL was generally well equipped, its tactics were largely theoretical and its operations hesitant and fragmented. The following document compiles these prewar Australian assessments, providing valuable insight into how Allied officers—such as Brown, Lieutenant General Sir John Lavarack, and Lieutenant General V. A. H. Sturdee—viewed their future Dutch ally on the eve of the Japanese invasion.

Breakdown of communication and stranded Australian troops

Australian troops still in Java were only informed about the Dutch surrender three days after the event, by that time it was too late for them to escape back to Australia and many were captured by the Japanese. Also KNIL units on Sumatra, Borneo, Celebes and the northern part of DNG kept on fighting. A key contribution that they made to the war effort was to destruct oilfield plants, airfields and ports. Some of the oilfields took many years to bring back to full operation, by that time the war was nearly over for Japaneses. This severely hampered the supply of the all important oil for their war machine. While the Japanese did get hold of most of the oilfield in British Malay, the Dutch had been able to do a more thorough demolition job in NEI.

The sad story for them was that as the British and Americans had abandoned ABDA there were no resources anymore available for the Dutch to undertake rescue missions to evacuate these stranded troops. They were either captured and killed by the Japanese or became POWs to be used as forced labour. Some units operating on northern parts of Dutch New Guinea (DNG) were able to retreat into the jungle and island hop to eventually find other units that could assist in evacuating them to Darwin, others joined units still operating on the smaller islands.

Thousands of Dutch (37.000) and Australian (22,000) servicemen ended up at the Burma–Thailand Railway, and worked in factories in Japan. They experienced extreme harsh conditions, inadequate food and forced labour. By the end of the war, some 8,000 Dutch and just over 8,000 Australian prisoners of war had died of disease, starvation or ill-treatment in Japanese hands.

Over 100,000 Dutch civilians, particularly women and children, were also interned by the Japanese, in exceptionally cruel conditions, for the remainder of the war. More than 13,000 died. After the war, thousands were send to Australia and New Zealand for a 3 or 6 months recuperation period, many at Camp Columbia in Brisbane . After their release, many former internees settled in Australia. For many the nightmare was not over after the Japanese defeat. Indonesian Nationalists kept Dutch people in the concentration camps in the areas they controlled. Many were only released during 1946 when the Allied Forces where able to take over control.

After the abandonment of ABDA there was a vacuum on the SE Asia war theatre and it was not until April that President Roosevelt announced the formation of South West Pacific Area (SWPA), after General MacArthur had fled to Australia and on the 30th of March he was appointed to Supreme Allied Commander South West Pacific Area, a command which included Australia and New Guinea in addition to Japanese-held areas.

The inter-governmental Pacific War Council was established in Washington on 1 April but remained largely ineffectual due to the overwhelming predominance of U.S. forces in the Pacific theatre throughout the war. The Dutch and Australian often complained that they were not involved or consulted in decisions made by the Council.

Those who were able to fled NEI and those stranded on ships – including members of the KNIL – were housed in re-grouping and training camps under the direct command of Dutch officers in Melbourne, Sydney, Brisbane and Casino.

Following the surrender there was one more military action which took place In late 1942. The KNIL tried to land in East Timor, to reinforce Australian commandos who were waging a guerrilla campaign, however it failed and ended with the loss of 60 soldiers, this was the last offensive action by the KNIL in NEI. However, guerillia activities from combined Australian and NEI (stranded) soldiers on the island continued for nearly another year.

The Z Special Unit kept operating in certain parts across the archipelago. This was a joint Allied special forces unit formed during the Second World War to operate behind Japanese lines in South East Asia. Predominantly Australian, it was a specialist reconnaissance and sabotage unit which included British, Dutch, New Zealand, Timorese and Indonesian members, predominantly operating in the NEI. Their involvement in the war was one of the most successful of the combined Australian-Dutch operations .

Paul Budde

Japanese air bases in Netherlands East Indies and the Philippines

Background resources on Netherlands -Indonesian relationship

Onsland.nl is a website providing access to over 250,000 sources on the shared history of the Netherlands and Indonesia, including digitized archives, photographs, and objects. These resources come from private collections and around 65 institutions, such as the National Archives, NIOD, and the Rotterdam City Archives. In the coming years, millions more sources will be added. The site offers educational materials, personal testimonies, and tools for family history research. It shares stories from various communities with ties to this history, including the Indo-Dutch, Moluccan, Chinese, and Papuan communities, focusing on World War II, decolonization, and their lasting impacts.

Onsland.nl meets a significant need for information, as nearly 2 million Dutch people have Indonesian roots or historical connections with Indonesia and want to explore this history. The website also serves general enthusiasts and educators, advancing the understanding of shared Dutch-Indonesian heritage.

The Metamorfoze program manages the digitization of these collections. To date, three rounds of applications have been held for individuals or institutions with Indo-Dutch heritage collections, resulting in over 1.5 million scans from ten institutions, with eight more collections currently in progress. By the end of the program, more than 4 million scans will have been made. Onsland.nl will continue to grow as new materials are added.

Onsland.nl is a project of the Digital Indo-Dutch Heritage Program, a collaboration between WO2Net, the Indisch Herinneringscentrum, and the KB National Library, funded by the Ministry of Health, Welfare, and Sport. Website.