Makassar centre of the trepang fishing

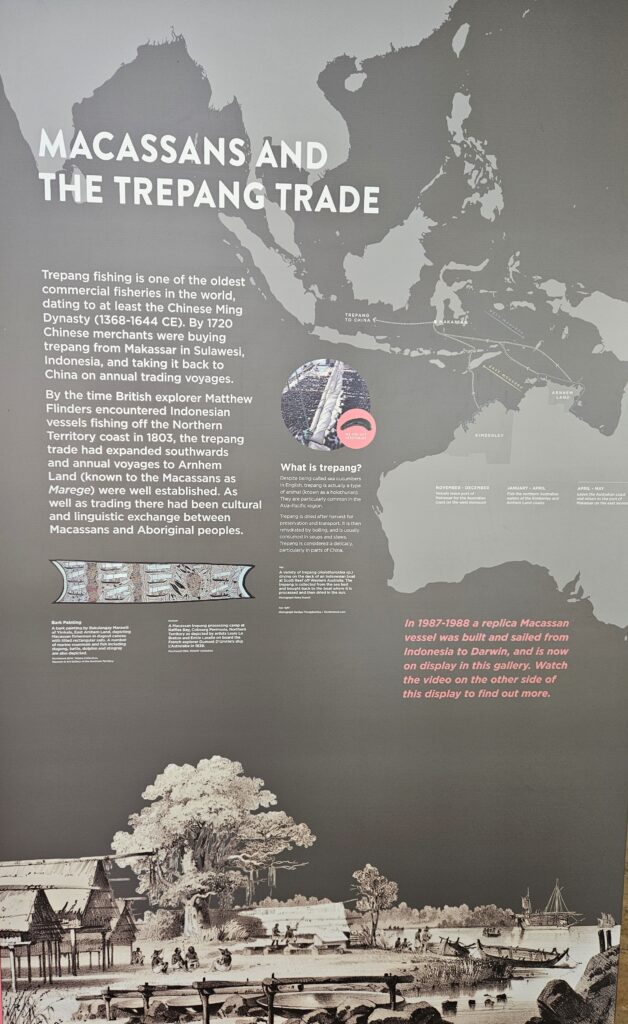

Trepang fishing, also known as sea cucumber fishing, is a type of fishing that involves the collection of sea cucumbers, which are a type of marine invertebrate. Sea cucumbers are typically found on the ocean floor and are harvested for a variety of purposes, including food and traditional medicine. They are known as sea cucumber, bêche-de-mer en Zeekomkommer in Dutch.

Trepang form large herds that move across specific features at the ocean floor, hunting for food. If you know these features, the harvesting of them becomes rather easy.

Trepang fishing is most commonly practiced in Southeast Asia, particularly in countries like Indonesia and Malaysia where it has been practiced for centuries. It is often carried out by local fishermen using traditional methods, such as diving and handpicking the sea cucumbers from the ocean floor. The collected sea cucumbers are then typically dried or processed before being sold or exported.

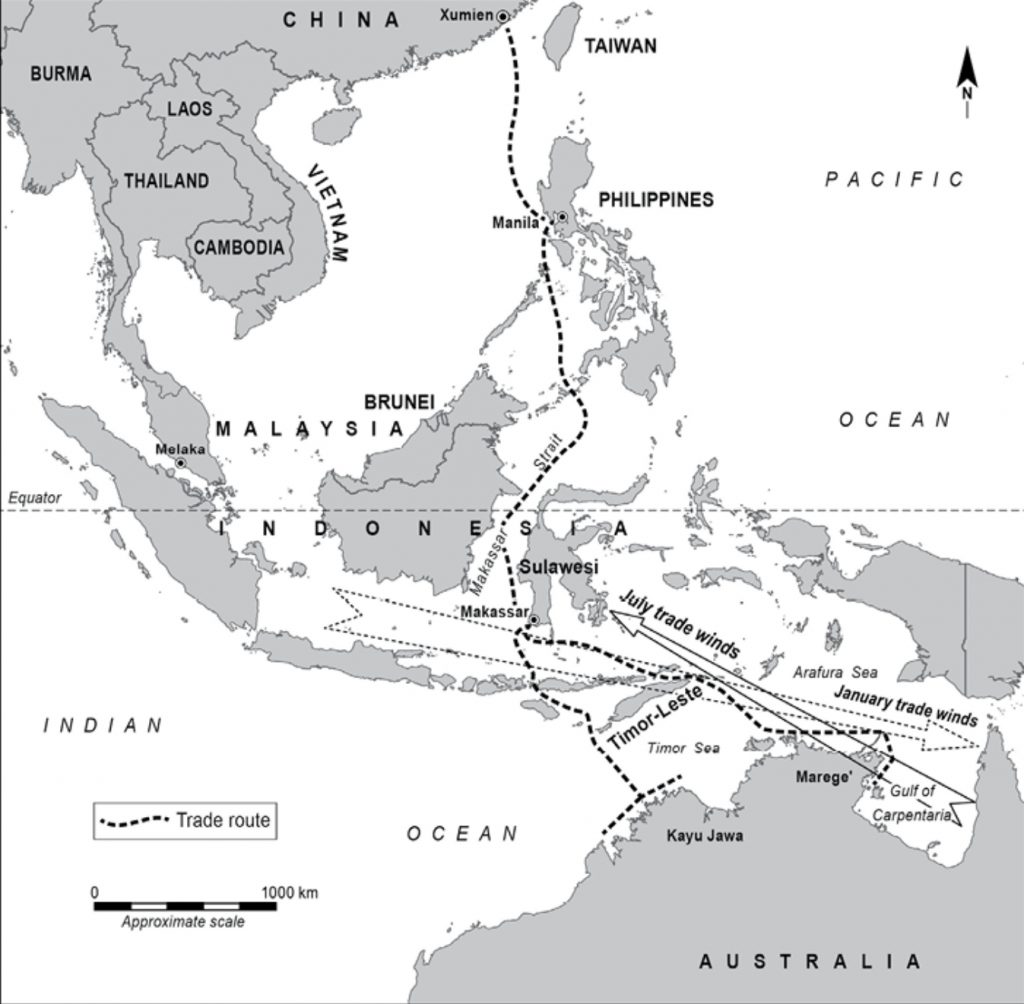

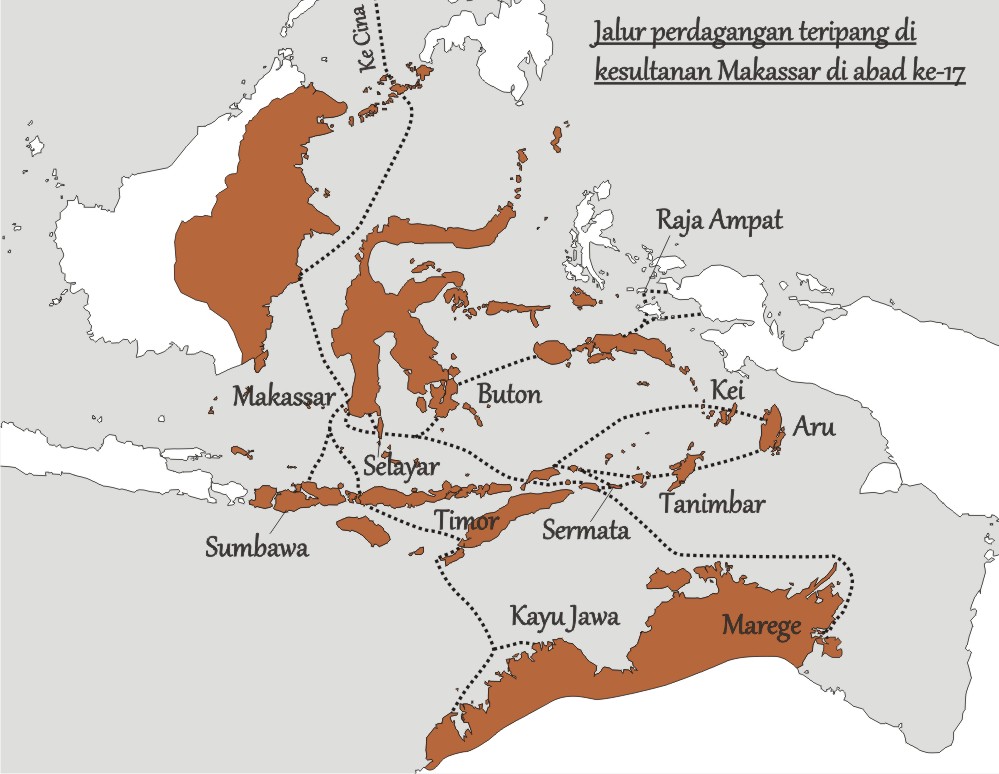

Makassar is positioned in the southwest peninsular of the Indonesian island Sulawesi (Celebes) at the crossroads of local trading routes to and from Java, Kalimantan, Maluku, Nusa Tenggara and the Philippines, and in long distance trade with Europe, India and China. They became the centre of the trepang fishery and the trepang trade.

Before the Dutch conquered Makassar, the area was part of the Gowa Kingdom, one of the most powerful kingdoms in SE Asia. It consisted of several smaller kingdoms who all had to pay tribute to the King of Gowa.

Dutch East Indies became the larger exporter of Trepang

The strategic importance of Makassar was seen by the VOC. The southwest point of the peninsula was ruled by the Kingdom of Bone. The Dutch utilised the ongoing conflicts over the control of the peninsula by the various kingdoms. Playing the various group out against each other allowed Gouverneur-Generaal Cornelis Speelman to conquer Makassar in 1669. In the process he had more than thirty villages burned down, and thousands of people were sold into slavery.

An important ally of the Dutch was the Kingdom of Bugis. The main ally of Makassar during the war was the northern Bugis state of Wajo. As was the case, their main ‘trades’ included piracy, slaves and trepang.

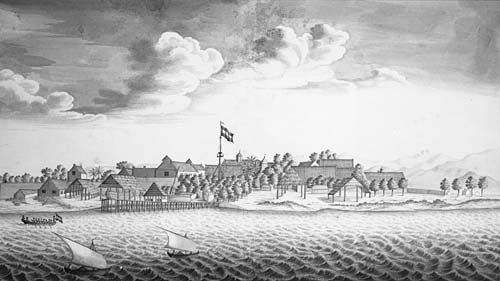

Since 1673 the area around the VOC Fort Rotterdam grew into a city currently known as Makassar. This basically ended the sovereignty of the powerful Kingdom Gowa (Makassar Sultanate), they even claimed the northern part of Australia as part of their kingdom. However, the Dutch never used that opportunity to claim that part for the VOC.

After they had established there power, the Dutch were only interested in trade and in the protection of their trading monopoly and did leave the local rulers in place to rule their kingdoms.

Makassar became an important trading post of the Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC – Dutch East Indies Company).

In 1824, the Dutch Governor-General of NEI Godert Alexander Gerard Philip, baron van der Capellen recorded that the trepang export from Makassar to China was worth DFL350,00 in todays value more the € 4 million). By the early 1880s, it was reported by the Dutch that the trepang export was the still the most important economic activity in the town, despite a significant reduction in trepang in comparison to the value at the start of that century, the Dutch Indies were still the largest exporter of trepang.

Abstract from Professor Campbell Macknight’s book ‘Strangers on the Shore’ page 138

| In 1824, Governor-General. van der Capellen reports that the trepang export from Makassar to China was worth about 350,000 guilders, still about 88 per cent of fine value in the 1780s. By the 1840s the trade had fallen away considerably. newly discovered source in the Jakarta archives gives detailed information on Makassar’s trade from 1840 to 1842. In 1842, for example, 43 vessels with a. total capacity of 446.5 lasten (893 tons) brought trepang worth 31,907 guilders from Marege’, but this was only 47 per cent of the .value of the total trepang imported. The total trepang export worth 114,867.50 guilders was still, the largest item of export, comprising nearly 15 per cent of the value of total. export, but this was worth only about 29 per cent of the figure from the 1780s. (See also Macknight 1976 for other statistics on the industry). |

Chinese demand for trepang drove the trade in this medicinal product

In the 2021 thesis Chinese Gustatory Revolution in Global History, 900-1840 for the Universtiteit Leiden, Guanmian XU also addresses the trepang trade. This is what Professor Campbell MacKnight wrote about it:

“What Dr Xu shows is how, first for pepper and later for trepang, changing Chinese medicinal theories gave rise to changes in consumption. These varying fashions in taste are firmly located in more general social, economic and political developments, not only in China, but also in Northeast and Southeast Asia. Dr Xu has read widely in a remarkable variety of languages.

In relation to the trepang trade I draw special attention to the remarks on chapter 4. In particular, this chapter explains how the trepang trade through Makassar, which was always the main market in island Southeast Asia, began in the 1690s [p.247]. The well-known reference to trepang and wax from the Southland in 1754 indicates that the trepang industry had extended to Australia by the middle of the eighteenth century. The earliest references to trepang Marege’ come from 1788 and 1789 [p.273].

This new account of how, why and when Chinese taste began to demand trepang, and especially trepang from island Southeast Asia, makes clear that any claim for a trepang industry in this area before the very late seventeenth century is unsupportable. An eighteenth-century origin for the Australian industry can now be taken as established.

Whether Southeast Asian vessels — except of course the Dutch East India Company vessels — visited the Australian coast before the eighteenth century is another question, but at least the crews of any such vessels were not looking for, or processing, trepang”.

Below is the summary of the thesis.

Trepang fishing in Australia mentioned in Dutch records

The activities of trepang fishermen from Makassar (Macassar) along Australian’s northern coasts is a well-known history event. It most likely started in the 18th century but will have increased significantly in the 19th century for reasons that will be explained below. Marege’ was the Makassan name for Arnhem land (meaning “Wild Country”), from the Cobourg Peninsula to Groote Eylandt in the Gulf of Carpentaria. Kayu Jawa was the name for the fishing grounds in the Kimberley region of Western Australia, from Napier Broome Bay to Cape Leveque.

The trepang fishermen also show up in the Dutch records of the VOC.

The first hint came from GW Earl, who wrote that the Dutch navigator Pieter Pieterson visited the Aru Islands (near Dutch New Guinea) in 1636 and had reported that the trepang fishery then merely existed.

It names the above mentioned Bugis as they key operators of this fishing business and mentioned that they had probably been visiting the Moluccas–namely the islands of the Kei group –since the sixteenth century and there is evidence that trepang fishing in this region actually started around this time.

It is possible that the support of the Bugis for the Dutch might have led to some sort of trepang fishing property rights which determined the right to capture sea cucumbers in certain areas. There are records that indicated that passes were provided to Bugis fishermen to collect trepang.

Many of the boats were owned by Dutch merchants ( such as De Grapp, Martieu, Seeso and Oeba). As the major customer of Trepang was China, the Chinese had a significant involvement in this trade and might also have been boat owners, most likely predating the Dutch involvement in the fishery. The Arabs were also involved but it is unclear when that started however in the 19th century they were together with the Dutch and Chinese mentioned as owners of the trepang fleets.

Once in charge of Makassar, the VOC was determined to gain control over the trepang trade and there are indications that restrictions were issued as early as 1667. However, they never completely succeeded in this. It also looks that the Chinese grip on this trade only strengthened over time.

The earliest Dutch record in Makassar that mentions trepang is in its official diary (daghregister) from June 1710. This entry refers to trepang collection off Buton in Southeast Sulawesi.

A VOC report from 1720, mentions vessels from Sulawesi and Flores looking for trepang near the islands of Luang and Moa in the Southern Moluccas. Their number was considerable, with 60 and 30 vessels, respectively.

Professor Charles Campbell Macknight conducted extensive research on the Indigenous peoples of northern Australia, including the Groote Eylandt region. In his 1969 book “The Voyage to Marege’: Macassan Trepangers in Northern Australia,” Macknight mentions the discovery of a Dutch coin and a piece of Dutch pottery at the Lyaba site off Groote Eylandt.

According to Macknight, the coin was a Dutch copper duit dating to 1742, and the pottery was a piece of blue and white earthenware that was likely produced in the Netherlands in the 18th century.

Yet, Professor Peter Boomgard concludes that trepang seemingly “appears out of nowhere” in 1720 in the records of the VOC. However, from the mid-eighteenth century on, there are frequent references in the Dutch records to the collection and processing of trepang all over Island Southeast Asia, with Makassar in South Sulawesi as the centre of the trade.

In the 1820s the Dutch Colonial naval vessel Doerga (Dourga) was sent by Netherlands East indies Government to northern Australia to establish Dutch claims to the region and to investigate the trepang trade.

This then easily leads to overfishing, especially if the activity takes place on a (semi) industrial scale, as it was reported by Casparus.Bosscher, He was a prolific writer of books and articles on Netherlands East Indies (NEI). He came to the NEI in 1840; in 1847 he entered the Civil Service, was appointed Resident of Ternate in 1857, of Manado in 1859, of Banka in 1861, of Madoera in 1867, of Kediri in 1872. In 1874 Director of the Dept of Education and Public Worship, in 1875 ditto of the Civil Service; he retired in 1876.

He remarked that in the islands of Aru, people would gather trepang at the same sand bank until the stock seemed to have been depleted.

Several of the above-mentioned sources also talk about a general decline in trepang trade between 1840–1850.

In 1824, the Dutch Governor of Malkassar Jan David van Schelle mentioned seeing Aboriginal visitors to Makassar, and noted that ‘they are very black, tall in stature, with curly hair, not frizzy like that of the Papuan peoples, long thin legs, thick lips and, in general, are quite well built’.

The Dutch recognised the overfishing and depletion of the trepang and enforced some regulations. Harvest restrictions were implemented by temporal closures of collection areas, and local overexploitation was avoided by travelling to other areas.

Around this time the Dutch Governor at Makassar also complained to the Brits that the tariffs and restrictions they were placing on the trepang trade with the Aboriginal tribes along the northern end western coast of Australia, severely hampered free trade.

Increased trepang fishing expeditions to Australia.

It can be expected that regulations started to come into force long before the local decline in trepang occurred. So therefore, it is expected that the fishermen started to venture out further and further to catch the animals. This is most likely the time when this brought them more and more in contact with Australia.

The absolute expert in this field Professor Charles Campbell Macknight mentioned to me (2023) that he now believes that the industry in Arnhem Land did not begin until about 1780.

Whatever the year might have been it is interesting to contemplate that already in this pre-European period, products from Australia reached Chinese markets, with the Dutch in one way or another being the middlemen.

Once the British start to arrive in Australia we also do get reports from sightings of these fleets and the trepang fishing activities. The British hydro-geographer Alexander Dalrymple was the first who, in 1768 specifically mentioned that it was the Bugis fishing along the Australian coast. Matthew Flinders came across such a fleet in 1803. On the way back he spend some time in Koepang on Timor where he also discussed the Trepang trade with the Dutch Governor.

The following is a report from Botanist Robert Brown who accompanied Flinders on his circumvention of Australia.

| “soon after we left the Gulph [of Carpentaria], in standing into a Bay formed by two islands, we were not a little surprised to observe 6 Praos [Perahus, Malay sailing boats] already at anchor. On the following day we went on board one of them and procured… some information relative to the object of their voyage … it appeared that they were part of a fleet of 60 sails belonging to the District of Bonij, in the Island of Celebes. They annually visit this coast, especially the Gulph of Carpentaria, along the western side of which we have observed many traces of them. The object of their voyage is the collecting of a marine animal … which they call Terrepang [trepang]. They find it in abundance and after preparing it, which is done by parboiling, then drying in the sun, and lastly smoke drying, they carry it to Timor Laut where they sell it to the Chinese who are either resident there or come on purpose for this commodity.” |

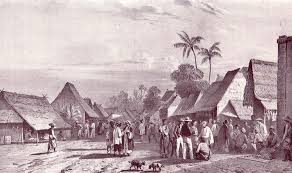

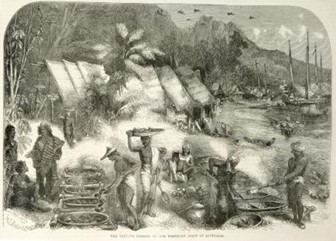

They would annually visit Australia using the north-west monsoon starting in December–travelled along the coast of northern Australia in search for trepang. They were equipped with all necessities to build small camps close to the shore, where they also erected smokehouses for the preparation of trepang.

Then, each April, as the monsoon winds began to blow, the fishermen departed, returning to Makassar carrying trepang to be traded north to China, where it is still used for food and medicine and is considered a culinary delight and an aphrodisiac.

The majorities of fishing gear and other supplies were brought-in from Makassar; including tobacco and other commodities for Aboriginal people who were to a small extent also employed. Only firewood for smoke-drying was gathered from mangroves in the area.

The Makassar fishermen also brought metal tools with them. Metal blades, knives and axes made everyday practices easier for the local Aboriginals along the coast in Arnhem land and Western Australia. This changed their way they started to cut food, making large dugout canoes and complex wooden sculptures.

The fishing method along the Australian coast was describes as follows: “… twelve large dredging canoes coming down before the wind, and hauling the great trepang dredgers … The twelve canoes, which were almost in line, had their immense mat sails hoisted on the triangular mast, and were gliding through the rippling water … while just beyond the canoes were four proas [perahus, praus, boats] at anchor, close to the beach, on which the Malay camp was formed.”.

This shows that the scale of these expeditions was a pre-industrial activity. This sometimes referred as the earliest industry in Australia.

It was estimated that by the time the trepang was largely depleted closer to their home, the Australian harvest consisted of about 900 tons – about one-third of the Chinese demand.

On the negative side the trepangers also introduces smallpox to the Aboriginal population they made contact with. While some of the Aboriginal people participated in the fisheries, it was mainly done by the Makasars and other people from this islands, Aboriginal people however, did receive gifts from the trepangers.

After Federation in 1901 the White Australian Policy was introduced, mainly aimed at banning Asian emigration to Australia. In 1906 the last perahu from Makassar visited Arnhem Land.

After the wars of independence with the Dutch, Makassar became, in 1945, part of the newly formed Republik of Indonesia.

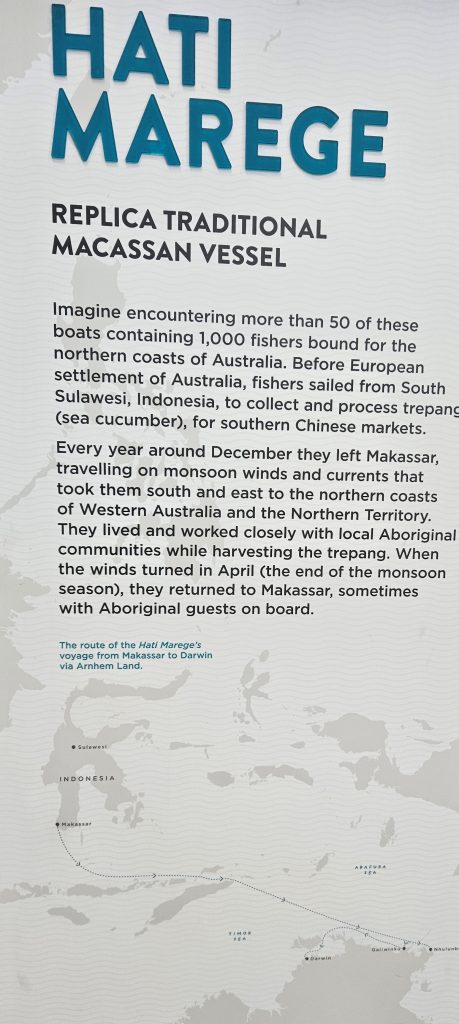

Hatti Marege

The Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory in Darwin also hosts a section on the Macassans. They also have on display the Hatti Marege, a replica of one of their sailing boats.

Hati Marege, meaning “Heart of Arnhem Land” is a replica of a typical 19th century Makassan perahu padewakang. It was built traditionally without any metal fastenings by the Kanjo boatbuilders of Tana Baru on the southeastern part of Sulawesi, Indonesia for the Australian Bicentennial celebrations in 1988, and was sailed to Darwin by a crew of 13. The five photos below were taken by Paul Budde in August 2023.

Lasting legacies

Aborigines returned with the trepangers to visit Makassar. Recent linguistic studies show that some Australian Aboriginal languages contain Makassan words.

An interesting one for this story is the word “Balanda” It is a term that refers to a non-Aboriginal or European person, commonly used by Aboriginal people, particularly those in the northern parts of Australia. The word “Balanda” was used by the Makassan traders, used to describe the Dutch by being an accented translation of “Hollander”.

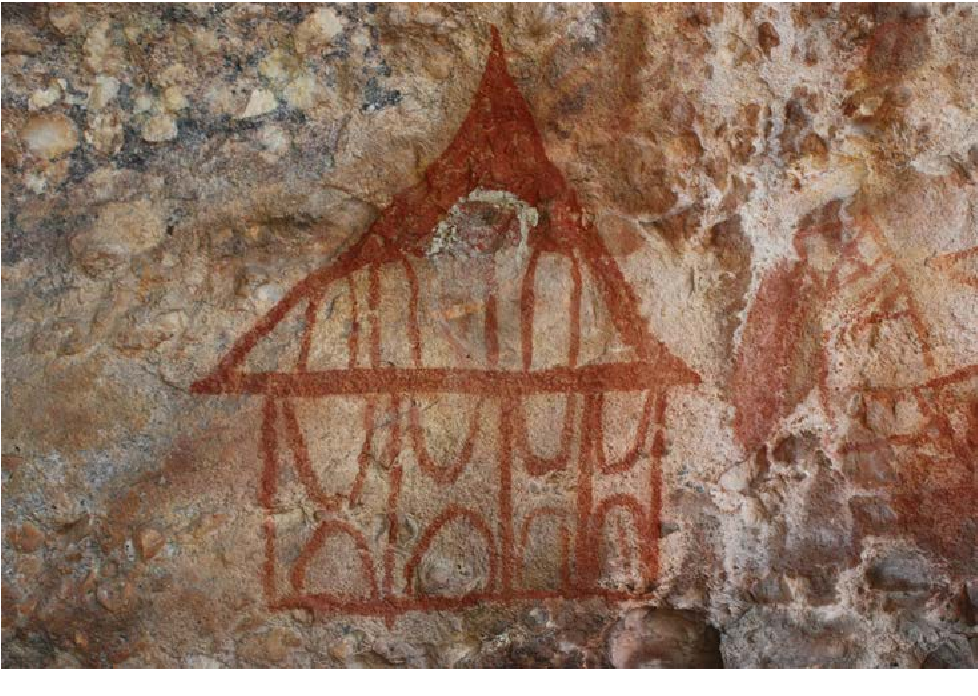

Aboriginal rock and bark paintings record the visit of the Makassans and their perahu. Another legacy of the Makassan trepangers is the tamarind trees (Tamarindus indicus) they planted from seeds that now grow wild along parts of the coast of northern Australia.

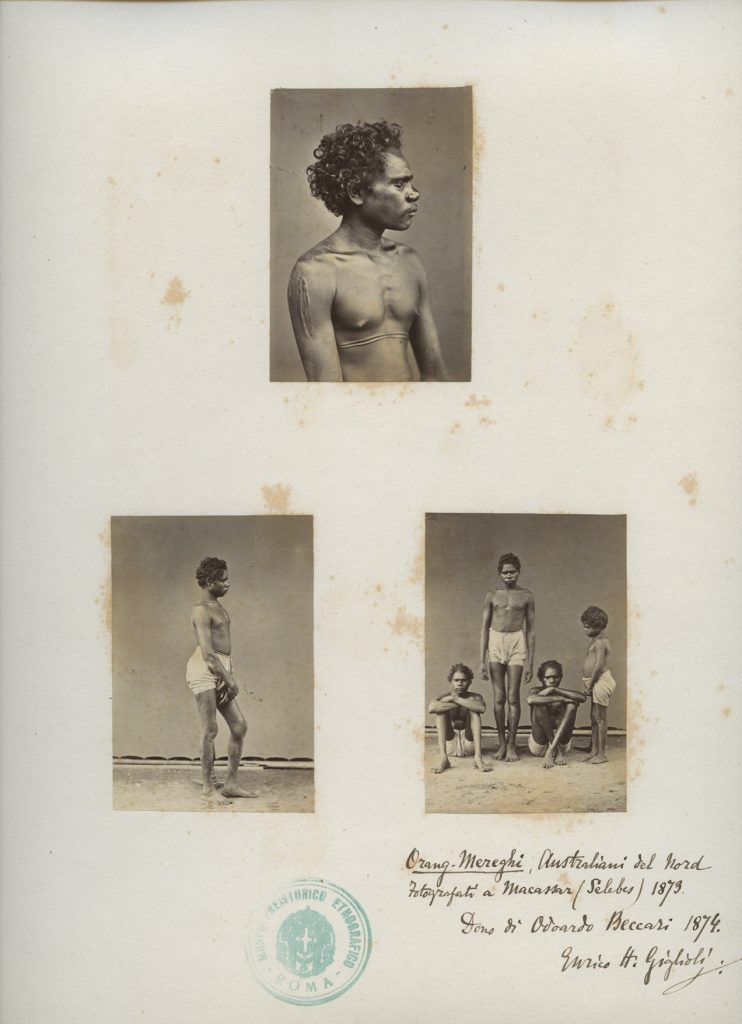

In 2023 photographs were published of Aboriginal people from the Cobourg Peninsula, in the port of Macassar in 1873. The Makassar called the Arnhem Land coast Marege’, and the Kimberley coast Kayu Jawa. The photographs were taken by the Italian naturalist Odoardo Beccari (1843–1920).

There are numerous accounts of this exchange by contemporaries, including from some Aboriginal people who participated in the trade. Charley Djaladjari from Cape Wilberforce on Elcho Island voyaged to Makassar around 1895, describing the presence of men and women who had settled and established families.

Many Malay fishermen also settled in Australia and became an integral part of the Asian-Australian relationships that had been built up over a period of 200 years. Malay were also among the pearl fishermen in Broome and many Chinese had also settled in the settlements along the Kimberley and Arnhem land coasts. These communities were totally disrupted during WWII as the area become a frontier in the Allied war against Japan. Most people were evacuated from these area including the many islands. Slowly in the 1970s and especially the 1990s relationships and communities were restored and are currently thriving with ongoing cultural exchanges.

The video below is from NITV (12 September 2011). For hundreds of years traders from Indonesia visited the northern coast of Australia to process Trepang or Sea Cucumber. Art exhibition in Melbourne has brought to light this legacy.

See also:

Fresh evidence emerges in search for descendants of Australia’s little-known overseas settlement

Paul Budde – February 2023

See also:

Notes on the southern voyages and settlements of the Sama-Bajau by James Fox

Monsoon traders: ships, skippers and commodities in eighteenth-century Makassar GJ Knaap, H Sutherland:

Photographing Macassan-Australian histories

Mixed Relations: Asian-Aboriginal Contact in North Australia – Regina Ganter

The voyage to Marege’– Professor Charles Campbell Macknight

Other sources as indicated in the text.