Most of Dutch history in Australia is linked to its explorers charting the country to the north, west and south. Shipwrecks from the Vereenigde Oost Indische Compagnie (VOC- Dutch East Indie Company) along the West Australian Coast adds another level to the story. The drama of the Batavia is an Australian first in many ways. A Dutch ship saved the fledgling NSW colony from starvation. WWII and Migration are other stories that will told elsewhere.The early history is linked to the VOC – the first international corporation – was established in 1602 with the aim to trade with the East Indies. The company had full support of the Dutch Government to use military force to establish trading posts and obtain produce from these places.

With my interest in Dutch-Australian history I have made several trips in search of places that are linked to this history. In various trips I visited places from Tasmania to Cape Leeuwin in the south to Broome and Arnhem Land in the north.

Initially the VOC ships followed the African and Asian coast lines to reach the East Indisch (now Indonesia). However, in 1611 Hendrik Brouwer, working for the VOC, discovered that sailing from Europe to The East Indies was much quicker if the Roaring Forties were used.

In 1607 they established their head office in Ternate (Moluccas Islands) and in 1619 they moved it to Batavia (now Jakarta).

However, the Dutch history of Australia does start in the north. Much of the following information comes from the various articles on Wikipedia.

Exploring North AustraliaThe Duyfken (Little Dove) – 1606

The first documented and undisputed European sighting of and landing in Australia was in late February 1606, by the Dutch navigator Willem Janszoon aboard the Duyfken. Janszoon charted the Australian coast and met with Aboriginal people. Janszoon followed the coast of New Guinea, missed Torres Strait, and explored and then charted part of the western side of Cape York, in the Gulf of Carpentaria, believing the land was still part of New Guinea.

On 26 February 1606, Janszoon and his party made landfall near the modern town of Weipa and the Pennefather River but were promptly attacked by the Indigenous people. Janszoon proceeded down the coast for some 350 km. He stopped in some places but was met by hostile natives and some of his men were killed.

At the final place, he initially had friendly relations with the natives, but after he forced them to hunt for him and appropriated some of their women, violence broke out and there were many deaths on both sides. These events were recorded in Aboriginal oral history that has come down to the present day. Here Janszoon decided to turn back, the place later being called Cape Keerweer, Dutch for “turnabout”.

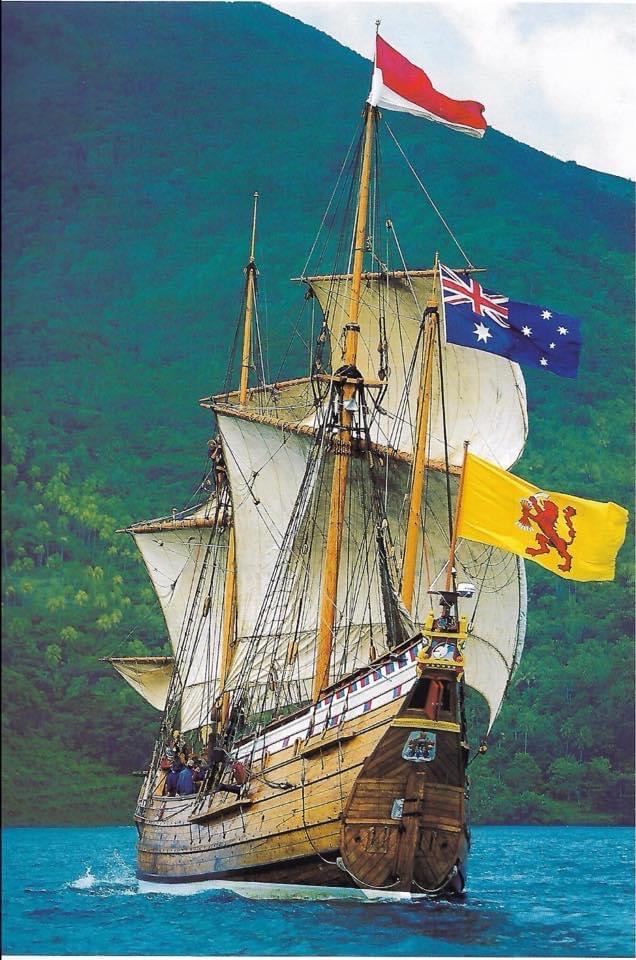

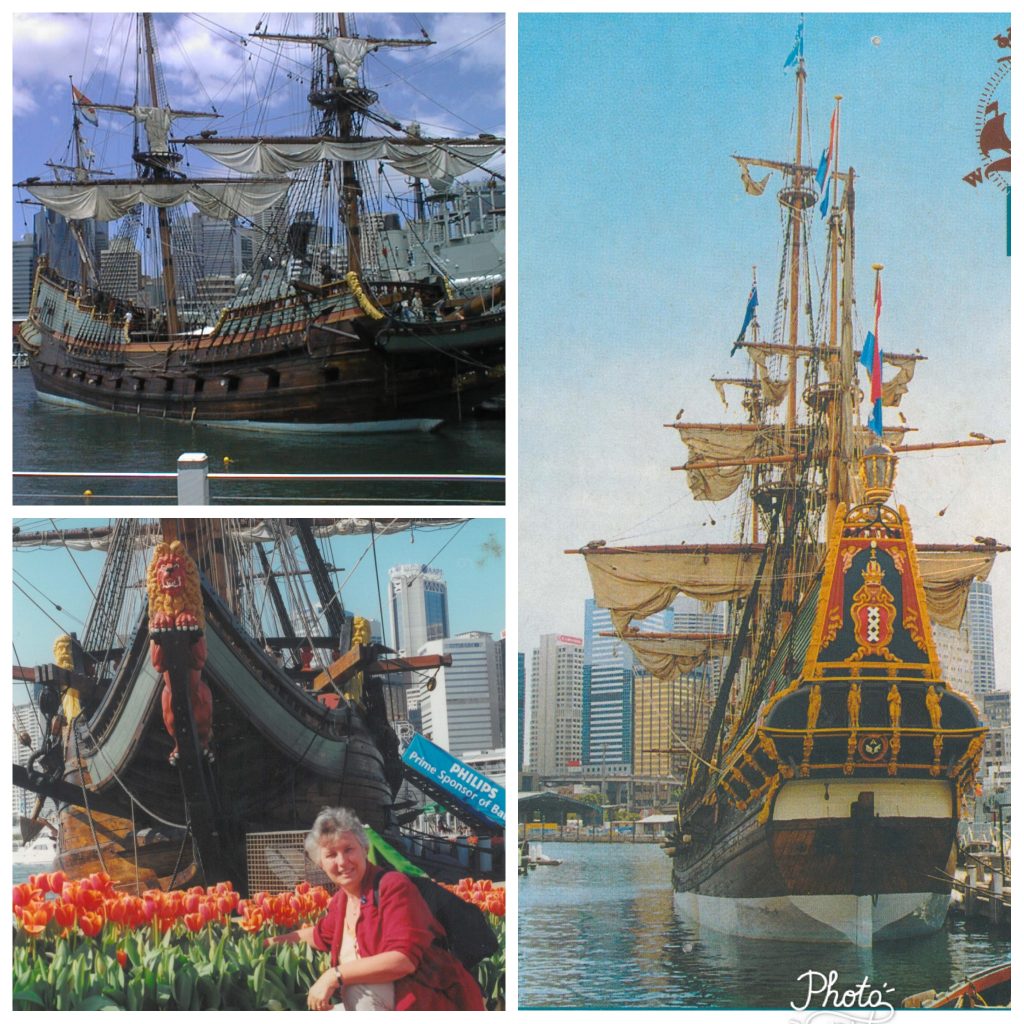

In the late 1990s an enthusiastic group of volunteers started to built a replica of the Duyfken and this boat has been sailing along the Australian coast and recently did find its permanenthome at the Australian National Maritime Museum in Sydney. In 2006 when it was moored in the harbour of Freemantle they needed people who during the night would stay on the Duyfken. Together with my Dutch friend Fred kappetijn we stayed the night on the ship. I still remember the cracking of the ship while floating on slight swell of the water as well as smell of ropes and tar.

Janszoon Carstensz – 1623

In 1623, Janszoon Carstensz was commissioned by VOC to lead an expedition to the southern coast of New Guinea and beyond, to follow up the reports of further land sighted by Janszoon in his 1606 voyages to the south.

Setting off from Amboyna in the Dutch East Indies with two ships, the Pera and Arnhem (captained by Willem Joosten Van Colster), he traveled along the south coast of New Guinea, then headed south to Cape York Peninsula and the Gulf of Carpentaria. On 14 April 1623, he passed Cape Keerweer. Landing in search of fresh water for his stores, Carstensz encountered a party of the local indigenous Australian inhabitants, who he described as “poor and miserable looking people” who had “no knowledge of precious metals or spices”. On 8 May 1623, Carstensz and his crew fought a skirmish with 200 Aborigines at the mouth of a small river near Cape Duyfken (named after Janszoon’s vessel which had earlier visited the region) and landed at the Pennefather River. Carstensz named the small river Carpentier River, and the Gulf of Carpentaria in honour of Pieter de Carpentier, Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies. Carstensz reached the Staaten River before heading north again. The Pera and Carstensz returned to Amboyna while the Arnhem crossed the Gulf of Carpentaria, sighting the east coast of Arnhem Land.

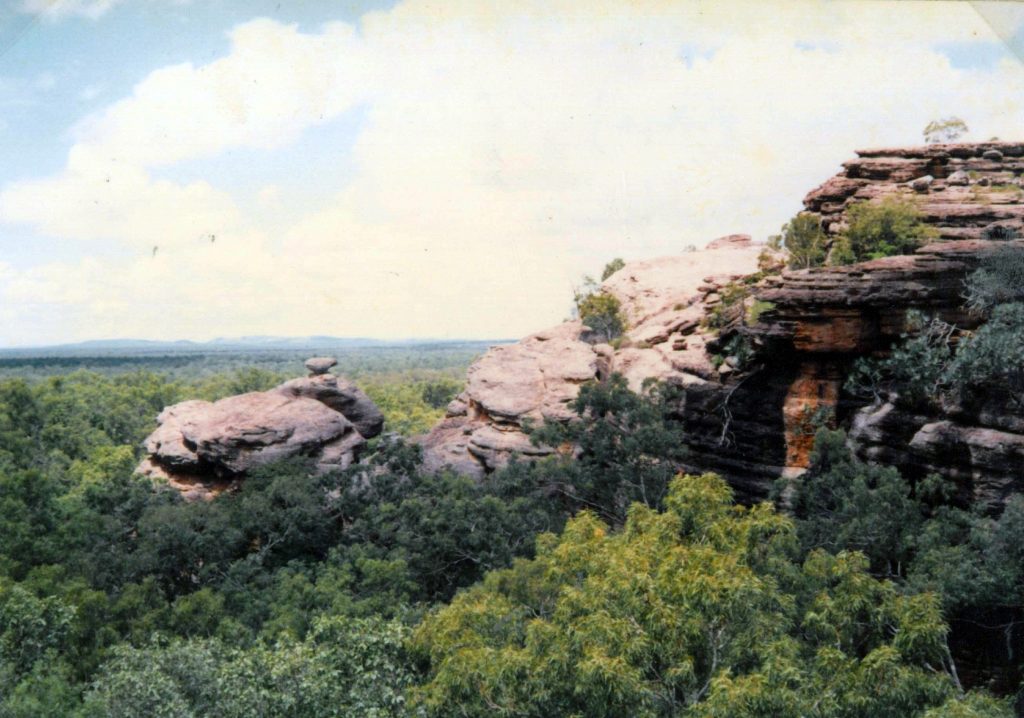

In 1988 I traveled from Darwin through Kakadu to to the edge of Arnhem Land (named after the ship and the town with the same name in the Netherlands).

The West Australian Coast, South Australia and Tasmania

Dirk Hartog – 1616

The new Brouwer’s route brought them from the Cape of Good Hope into the Roaring Forties (at 40–50° latitude south), then sailing east before turning north to Java using the South Indian Ocean Current. The problem with the route, however, was that there was no easy way at the time to determine longitude, making Dutch landfalls on the west coast of Australia inevitable, as well as ships becoming wrecked on the shoals. Most of these landfalls were unplanned.

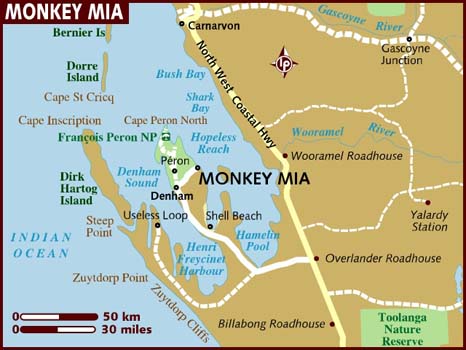

The first such landfall was in 1616, when Dirk Hartog, employed by VOC, reached land at Shark Bay (on what is now called Dirk Hartog Island) off the coast of Western Australia. Finding nothing of interest, Hartog continued sailing northwards along this coastline of Western Australia previously unknown to Europeans, making nautical charts up to about 22° latitude south. He then left the coast and continued to Batavia. He called Australia T Landt van d’Eendracht (shortened to Eendrachtsland), after his ship, a name which would be in use until Abel Tasman named the land New Holland in 1644.

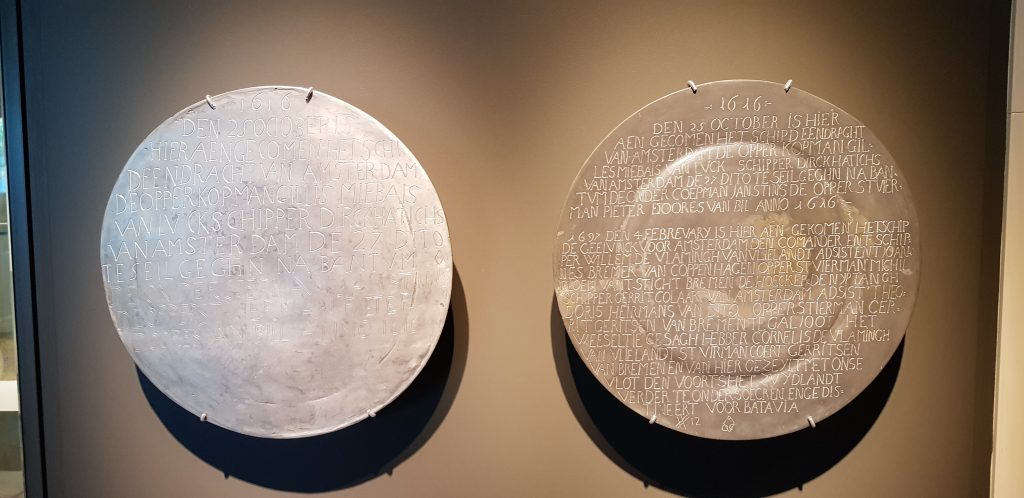

Pewter plaques – Dirk Hartog Island

| Australia’s oldest European maritime relic is a Dutch pewter dish that was nailed to a timber post 400 years ago on remote Dirk Hartog Island in Shark Bay. Now housed at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam and still bearing its inscription, the historic pewter dish was left by the crew of the Eendracht to record their visit to the ‘South Land’ on 25 October 1616. On 2 February 1697, Dutch seafarer Willem de Vlamingh’s crew found Hartog’s ‘calling card’ partly buried in sand at the base of the wooden post overlooking Cape Inscription. De Vlamingh (or possibly his senior merchant) recognised the historic value of the Eendrachtdish and took it on board replacing it with another flattened and inscribed pewter dish. The 1697 dish was inscribed with a copy of the text from the 1616 dish. To that was added details of the three-day visit to the island by de Vlamingh and his crew. |

Frederik de Houtman 1606 and 1619

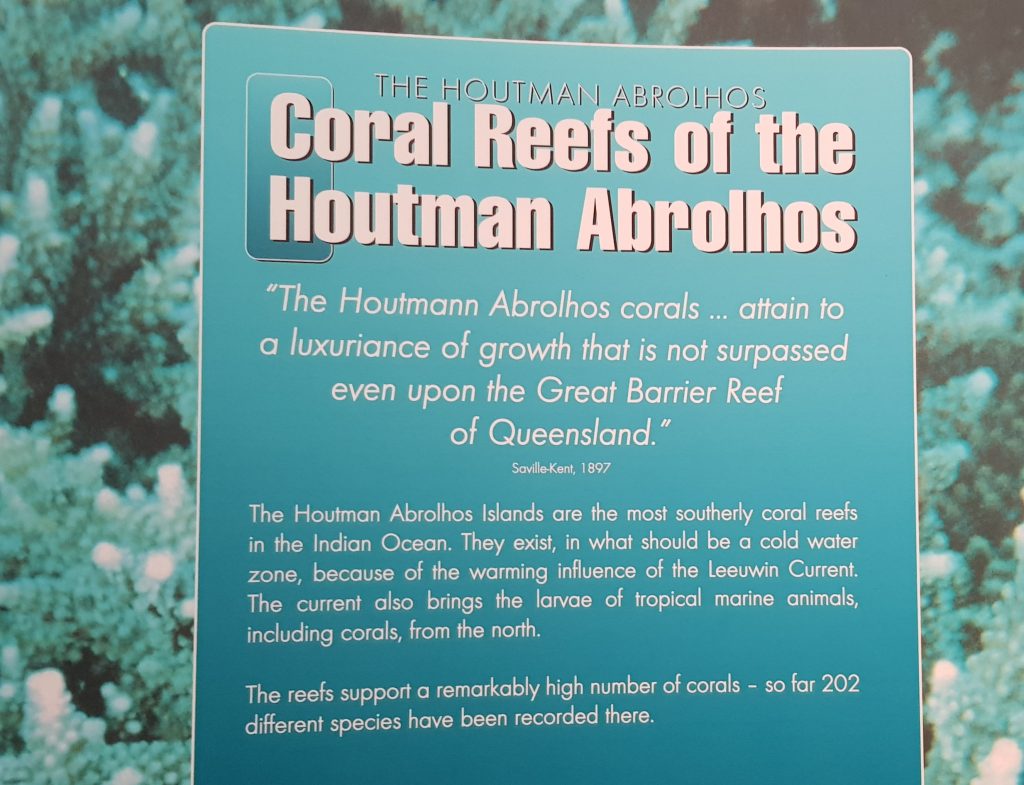

in 1606. Discovery of the Houtman Abrolhos islands is credited to Frederick de Houtman, Captain-General of Dordrecht, as it was Houtman who later wrote about the discovery in a letter to the directors of the Dutch East India Company:

“On the 29th do. deeming ourselves to be in an open sea, we shaped our course north-by-east. At noon we were in 29° 32′ S. Lat.; at night about three hours before daybreak, we again unexpectedly came upon a low-lying coast, a level, broken country with reefs all round it. We saw no high land or mainland, so that this shoal is to be carefully avoided as very dangerous to ships that wish to touch at this coast. It is fully ten miles in length, lying in 28° 46.”

In 1619, the same Houtman, in the same ship Dordrecht, and Jacob d’Edel, in another VOC ship Amsterdam, sighted land on the Australian coast near present-day Perth which they called d’Edelsland. After sailing northwards along the coast, they made landfall in Eendrachtsland, which had previous been encountered and named by Hartog, before turning for Batavia.

In 1627, François Thijssen ended up too far south and on 26 January 1627 he came upon the coast of Australia, near Cape Leeuwin, the most south-west tip of the mainland. Pieter Nuyts the VOC official aboard his ship gave Thijssen permission to continue to sail eastwards, mapping more than 1,500 kilometres of the southern coast of Australia from Albany, Western Australia to Ceduna, South Australia. He called the land ‘t Land van Pieter Nuyts (The Land of Pieter Nuyts). Part of Thijssen’s map shows the islands St Francis and St Peter, now known collectively with their respective groups as the Nuyts Archipelago.

The Leeuwin – 1622

Leeuwinne (Lioness) was a Dutch galleon that discovered and mapped some of the southwest corner of Australia in March 1622. It was the seventh European ship to sight the continent.

Leeuwin’s logbook has been lost, so very little is known of the voyage. However, recently(2022) Dr Nonja Peters discovered the naam of the schipper: Jan Fransz. VOC letters indicate that the voyage from Texel to Batavia took more than a year, whereas other vessels had made the same voyage in less than four months; this suggests that poor navigation may have been responsible for the discovery.The same is suggested by the 1644 instructions to Abel Tasman, which states that

“[I]n the years 1616, 1618, 1619 and 1622, the west coast of the great unknown South-land from 35 to 22 degrees was unexpectedly and accidentally discovered by the ships d’Eendracht, Mauritius, Amsterdam, Dordrecht and Leeuwin, coming from the Netherlands.”

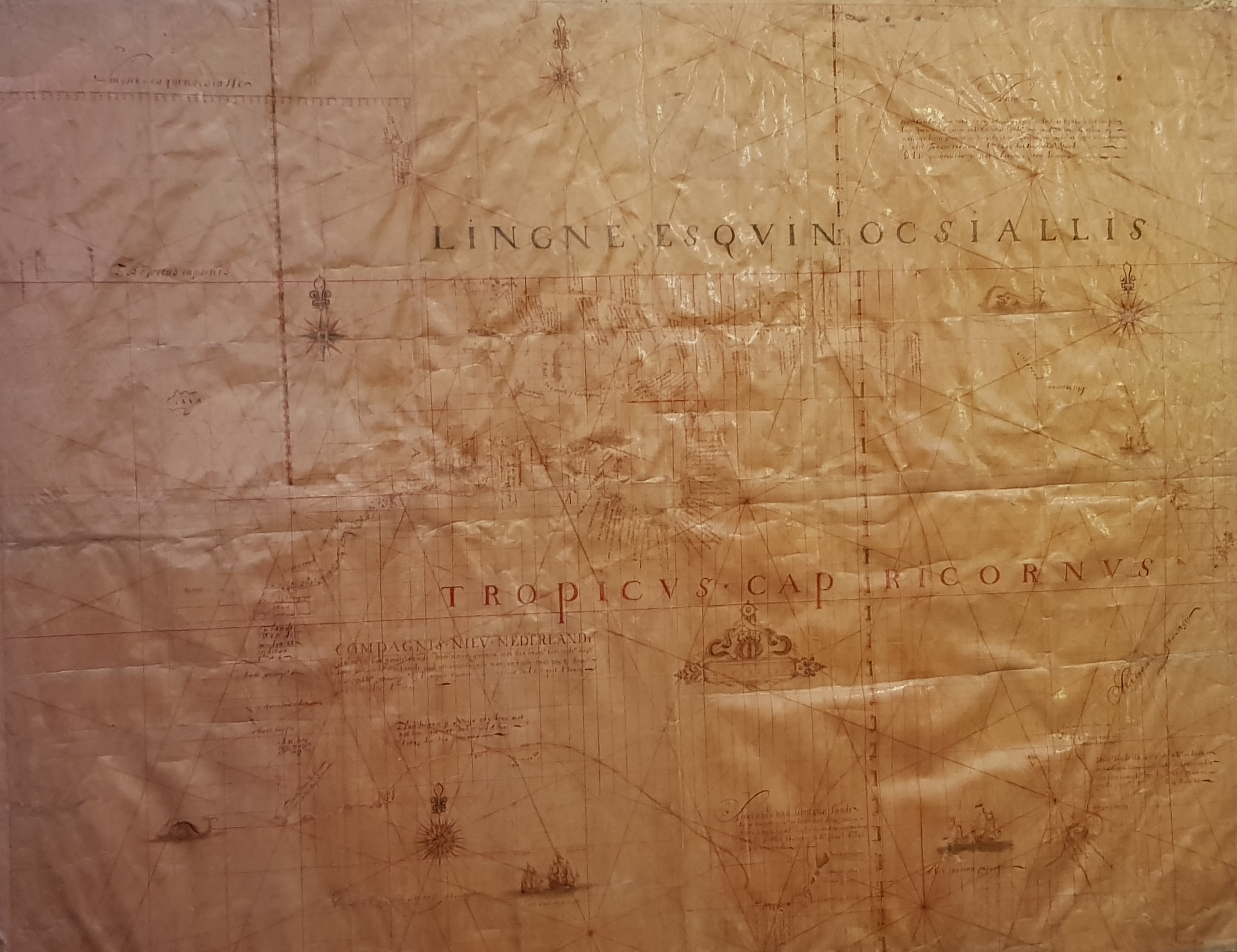

The land discovered by Leeuwin is recorded in Hessel Gerritsz’ 1627 Caert van’t Landt van d’Eendracht (Chart of the Land of Eendracht). This map includes a section of coastline labelled ‘t Landt van de Leeuwin beseylt A° 1622 in Maert (“Land made by the ship Leeuwin in March 1622”), which is thought to represent the coast between present-day Hamelin Bay and Point D’Entrecasteaux. Portions of this coastline are labelled Duynich landt boven met boomen ende boseage (“Dunes with trees and underwood at top”), Laegh ghelijck verdroncken landt (“Low land seemingly submerged”) and Laegh duynich landt (“Low land with dunes”).

The south-west corner of Australia was subsequently referred to by the Dutch as ‘t Landt van de Leeuwin (“The Land of the Leeuwin”) for a time, subsequently shortened to “Leeuwin’s Land” by the English. This name Leeuwin still survives in the name of Cape Leeuwin, the most south-westerly point of the Australian mainland, so named by Matthew Flinders in December 1801.

The pictures above were made in 2003 at a trip along the West Australian Coast from Perth to Cape Leeuwin and Albury.

Francois Thijssen – 1626

The Gulden Zeepaert (Golden Seahorse) sailed from the Netherlands on 22 May 1626, under the command of Francois Thijssen. Also on board was Pieter Nuyts, extraordinary member of the Dutch East India Company’s Council of India, their executive body in the East Indies.

It appears that in January 1627 the vessel encountered the Southland in the vicinity of Cape Leeuwin. Instead of turning north to make for Batavia, as required by Dutch ships of this period, it continued along the south coast of Australia for 1,800 kilometres. They reached St. Francis and St. Pieter Islands in what is now known as the Nuyts Archipelago, off Ceduna in South Australia.

The region they encountered became known as Nuyts Land. Nuyts had also been on board the Leeuwin which sighted and named Cape Leeuwin in 1622. The ship was the 13th recorded European contact with Australia.

The Batavia – 1629

The Batavia, built in Amsterdam in 1628 was the company’s new flagship, she sailed that year on her maiden voyage for Batavia. On 4 June 1629, the Batavia was wrecked on the Houtman Abrolhos, a chain of small islands off the coast of Western Australia.

Five days after the disaster happened, Commander Francisco Pelsaert and skipper Arien Jacobsz with forty six others left in the ship’s longboat to search for water, ending up in Batavia and not returning for three and a half months, during which time a massacre occurred.

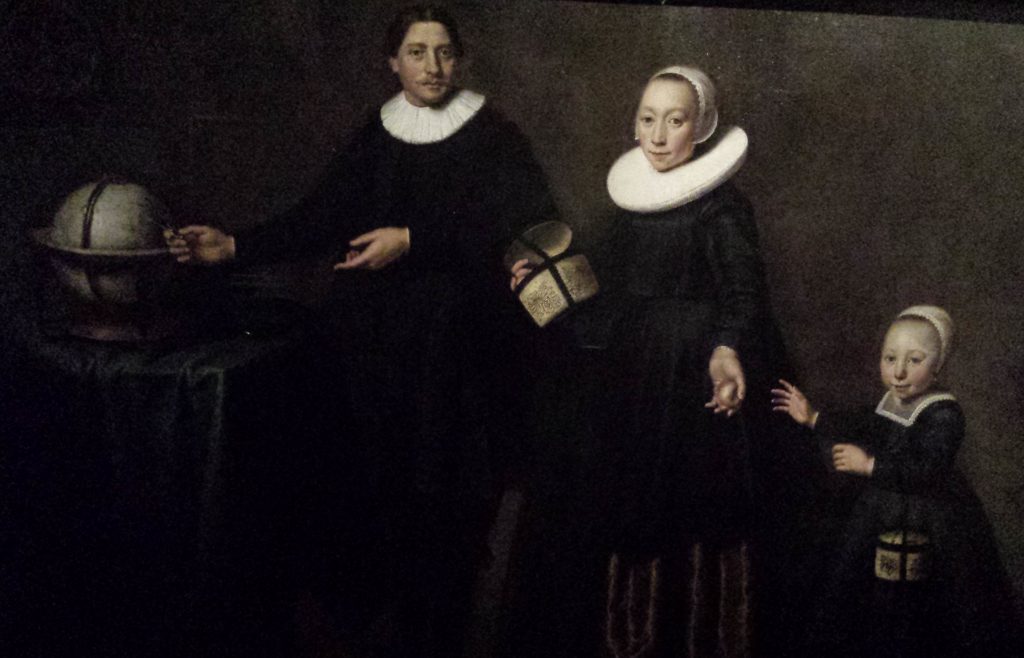

Francisco Pelsaert (c. 1595 – September 1630)

| A Dutch merchant who worked for the Dutch East Indies Company, who became most famous as the commander of the ship Batavia, which ran aground in the Houtman Abrolhos off the coast of Western Australia in June 1629. |

Following the Batavia shipwreck in 1629, a group of the marooned soldiers under the command of Wiebbe Hayes were put ashore on West Wallabi Island to search for water. The mutineers were secretly hoping that they would starve or die of thirst. However the soldiers were able to wade to neighbouring East Wallabi Island, where there was a fresh water spring. Furthermore, West and East Wallabi Island are the only islands in the group upon which the tammar wallaby lives. Thus the soldiers had access to sources of both food and water that were unavailable to the mutineers.

Later the mutineers mounted a series of attacks on the soldiers, which they were able to repulse. The remnants of improvised defensive walls and stone shelters built by Wiebbe Hayes and his men on West Wallabi Island are oldest surviving European buildings in Australia. The remnants of “the fort” are nothing more than a tiny, sandstone-coloured rectangle in the scrub about 100 metres from the sea. It is unimpressive and isolated and yet this simple structure, just some loose rocks piled up to make a simple fortress, saved the survivors of the Batavia.

Escapees from the bloodshed on Beacon Island alerted Hayes, and he organised the defence of his companions, repelling attacks from Cornelisz.

Above, Wiebe Haye’s fortress on East Wallabi Island from the air, fortress circled in red. To the right a replica of the fortress in Batavia Park, Geraldton.

Middle picture. In recognition of his role the Batavia Coast Maritime Heritage Association (BCMHA) raised funds and arranged for the sculpting and casting of the statue in 2009. The statue shows a defiant Hayes bearing one of the pikes the Defenders had made.

The pictures above are made in 2018 remembering Wiebe Hayes and the first European ‘building’ on Australian ground. Wiebe was born about 1608, he was a colonial soldier from Winschoten, Netherlands. He became a national hero after he led a group of soldiers, sailors and other survivors of the shipwreck of the Batavia against the murderous mutineers led by Jeronimus Cornelisz .

In October, at the height of their last and deadliest battle, when Hayes and his men were able to capture Cornellisz they were interrupted by the return of Pelsaert aboard the Sardam. Hayes raced ahead of the remaining mutineers to warn him of their plans to overwhelm the rescue ship. Cornelisz denied all charges but there was plenty of evidence from the survivors to the contrary.

Pelsaert subsequently tried and convicted Cornelisz and six of his men, who became the first Europeans to be legally executed in Australia. Two other mutineers, convicted of comparatively minor crimes, were marooned on mainland Australia, thus becoming the first Europeans to permanently inhabit the Australian continent. Of the original 332 people on board Batavia, only 122 made it to the port of Batavia.

Below is an overview of the three groups of photos .

In 2000 the Batavia was transported by ship to Australia, where it took part in the celebrations surrounding the 2000 Olympics in Sydney. The photos in the group to the left are made at that time.

The photo in the middle depicts the large-scale embroidered work – known as the Batavia tapestry – by Melbourne textile artist Melinda Piesse. It was on display in the Australian National Maritime Museum in Sydney in 2017.

The group of four photos to the right shows pictures of the Houtman Abrohlos. All these pictures were made during a flight over the islands in 2018.

Top left: overview of the Pelseart Group of Islands, the southernmost of the three groups of islands that make up the Houtman Abrolhos island chain. It was here where the drama of the Batavia unfolded.

Top right: Morning Reef near Beacon Island where the Batavia was shipwrecked.

Bottom left: Beacon Island known as the Batavia Graveyard, it is here that most victims of Cornelisz were killed. There is currently archaeological works taken place in relation to the remains. For that purpose all fisherman’s huts that have build during the mid 1900s have been removed from the island.

Bottom right: Long Island. Pelsaert decided to conduct his trials on the islands, because the Sardam on the return voyage to Batavia would have been overcrowded with survivors and prisoners. After a brief trial, the worst offenders were taken to Seal Island (now called Long Island) and executed. Cornelisz and several of the major mutineers had both hands chopped off before being hung. Bottom right: Gun Island

In 2018 we flew to Geraldton and from here we toured the Shipwreck Coast to Dirk Hartog Island to the north. We flew over the Pelsaert Group of islands where the drama with the Batavia happened. Geraldton has an excellent museums with a large section dedicated to the Batavia and other shipwrecks. Batavia Park, dedicated to people who died in the massacre was opened in 2013, 50 years after the discovery of the wreck by Max Weber.

Abel Tasman 1642 and 1644

In August 1642, VOC despatched Abel Tasman and Franchoijs Visscher on a voyage of which one of the objects was to obtain knowledge of “all the totally unknown provinces of the kingdom of Beach”. This expedition used two small ships, the Heemskerck and the Zeehaen. Starting in Mauritius both ships left on 8 October using the Roaring Forties to sail east as fast as possible.

On 7 November, because of snow and hail the ships’ course was altered to a more north-eastern direction. On 24 November 1642 Abel Tasman sighted the west coast of Tasmania, north of Macquarie Harbour. He named his discovery Van Diemen’s Land after Antonio van Diemen, Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies. Proceeding south he skirted the southern end of Tasmania and turned north-east, Tasman then tried to work his two ships into Adventure Bay on the east coast of South Bruny Island where he was blown out to sea by a storm, this area he named Storm Bay.

On 7 November, because of snow and hail the ships’ course was altered to a more north-eastern direction. On 24 November 1642 Abel Tasman sighted the west coast of Tasmania, north of Macquarie Harbour. He named his discovery Van Diemen’s Land after Antonio van Diemen, Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies. Proceeding south he skirted the southern end of Tasmania and turned north-east, Tasman then tried to work his two ships into Adventure Bay on the east coast of South Bruny Island where he was blown out to sea by a storm, this area he named Storm Bay. Two days later Tasman anchored to the north of Cape Frederick Hendrick just north of the Forestier Peninsula. Tasman then landed in Blackman Bay – in the larger Marion Bay. The next day, an attempt was made to land in North Bay; however, because the sea was too rough the carpenter swam through the surf and planted the Dutch flag in North Bay. Tasman then claimed formal possession of the land on 3 December 1642.

After some exploration, Tasman had intended to proceed in a northerly direction but as the wind was unfavourable he steered east. On 13 December 1642 they sighted land on the north-west coast of the South Island, New Zealand, becoming the first Europeans to sight New Zealand. Tasman named it Staten Landt “in honour of the States General” (Dutch parliament).

The expedition then sailed north, sighting Cook Strait, which it mistook for a bight and named “Zeehaen’s Bight”. Two names that the expedition gave to landmarks in the far north of New Zealand still endure: Cape Maria van Diemen and Three Kings Islands. Maria was the wife of his patron, Anthony van Diemen, Governor General of Batavia

In 1644 Tasman commanded the Limmen, Zeemeeuw and Bracq on a second voyage to New Holland. Leaving Banda in February 1644, he sailed along the southern coast of New Guinea, but failed to discover Torres Strait. He then charted the Gulf of Carpentaria and the northern and western coasts of Australia as far as North West Cape. He returned to Batavia in August 1644. The expedition covered a huge stretch of coastline, but because it sailed some distance from the coast it failed to establish that Croker, Melville and Bathurst and various other islands were in fact islands. Tasman was a member of the Council of Justice of Batavia in 1644-1648. In 1648-1649 he led a fleet of ships with the intention of attacking Spanish vessels in the Philippines, but the expedition had only limited success. In his last years he was a merchant in Batavia.

The Vergulde Draeck – 1656

On the night of the 28 April 1656, the Vergulde Draeck struck a submerged coral reef midway between what are now the coastal towns of Seabird and Ledge Point, Western Australia. On board were 193 crew, eight boxes of silver coins worth 78,600 guilders and trade goods to the value of 106,400 guilders.

Of the 193 crew, 118 are believed to have perished. The initial 75 survivors, including the ship’s captain Pieter Albertszoon, and the under steersman, made it to shore. They had with them the ship’s boat, a schuyt, along with a small number of provisions and stores washed on shore. Nine days later the under steersman and six crew members were dispatched to Batavia to summon help.

After a journey of some 1,400 nautical miles (2,600 km), lasting 41 days, with little water, little food and suffering from exposure, they arrived at Batavia. The alarm was raised and the search for the survivors of the Vergulde Draeck and cargo began.

On 23 April 1657, the Vinck was send on a rescue mission, but no survivors or wreckage was found.

On 1 January 1658, the Waeckende Boey and the Emeloordt were dispatched from Batavia. This time the rescue attempt was made in the more favourable summer months. On returning from the coast, they recorded the discovery of wreckage believed to be of the Vergulde Draeck. Most notable was a plank circle, a collection of some 12 to 13 planks placed in a circular fashion, dug into the beach sand with their ends facing skyward. During the various searches, a small shore party from the Waeckende Boey led by Abraham Leeman became separated. Bad weather prevented Leeman from returning to the Waeckende Boey and after four days Leeman and his party were assumed lost. The modern town of Leeman, Western Australia is named after this Dutch explorer.

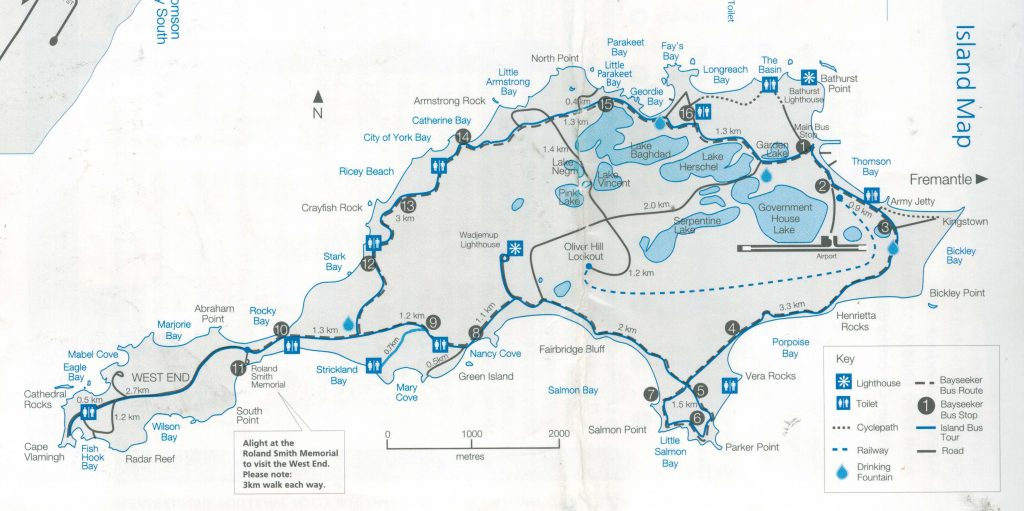

13 Dutch sailors including Abraham Leeman van Santwits from the Waeckende Boey landed on Rottnest Island near Bathurst Point on 19 March 1658 while their ship was careened nearby.

On 9 March 1658, Captain Jonck of the Emeloordt managed to send a small party to land. Upon returning, the shore party reported having seen three Aboriginal natives of tall stature who attempted to communicate with them using basic hand signals. This story of ‘first contact’ was a peaceful exchange, likely with the Yuet people of Western Australia.

A further rescue attempt was made in 1659 by the vessel Emmenhorn but no sign of survivors or wreckage was found.

Willem de Vlamingh – 1696

In 1696, De Vlamingh commanded the rescue mission to Australia’s west coast to look for survivors of the Ridderschap van Holland that had gone missing two years earlier. There were three ships under his command: the frigate Geelvink, captained by De Vlamingh himself; the Nijptang, under Captain Gerrit Collaert; and the galiot Weseltje, under Captain Cornelis de Vlamingh, son of Willem de Vlamingh.

On 29 December 1696, De Vlamingh’s party landed on Rottnest Island. He saw numerous quokkas, and thinking they were large rats he named it ‘t Eylandt ‘t Rottenest (“Rats’ Nest Island”). He afterwards wrote of it in his journal:

“I had great pleasure in admiring this island, which is very attractive, and where it seems to me that nature has denied nothing to make it pleasurable beyond all islands I have ever seen, being very well provided for man’s well-being, with timber, stone, and lime for building him houses, only lacking ploughmen to fill these fine plains. There is plentiful salt, and the coast is full of fish. Birds make themselves heard with pleasant song in these scented groves. So, I believe that of the many people who seek to make themselves happy, there are many who would scorn the fortunes of our country for the choice of this one here, which would seem a paradise on earth”.

Rottnest Islands with the quokkas – 2003

On 10 January 1697, he ventured up the Swan River. He and his crew are believed to have been the first Europeans to do so. They are also assumed to be the first Europeans to see black swans, and De Vlamingh named the Swan River (Zwaanenrivier in Dutch) after the large number they observed there. The crew split into three parties, hoping to catch an Aborigine, but about five days later they gave up their quest to catch a “South lander”.

On 22 January, they sailed through the Geelvink Channel. The next days they saw ten naked, black people. On 24 January they passed Red Bluff. Near Wittecarra they went looking for fresh water. On 4 February 1697, he landed at Dirk Hartog Island, Western Australia, and replaced the pewter plate left by Dirk Hartog in 1616 with a new one that bore a record of both of the Dutch sea-captains’ visits.

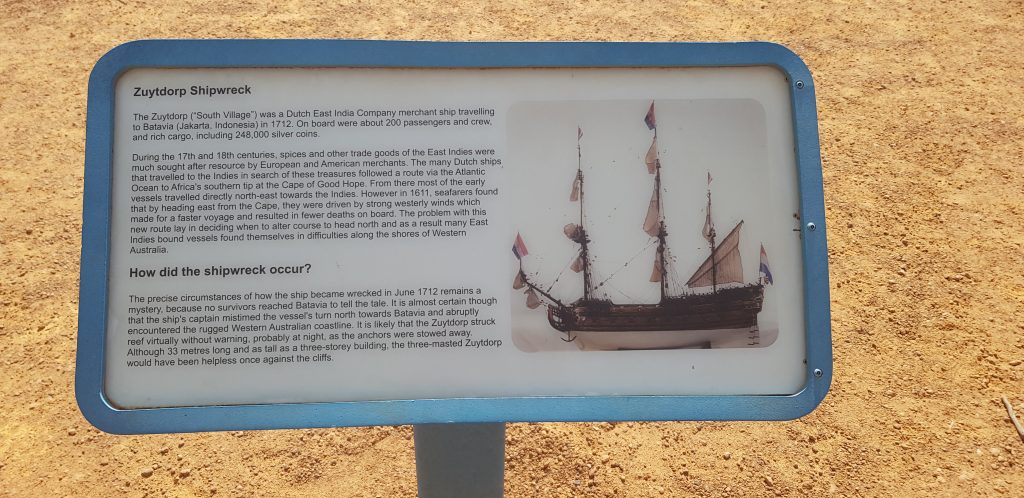

The Zuytdorp – 1711

On 1 August 1711 the ship the Zuytdorp left the Netherlands with a load of freshly minted silver coins. The ship never arrived at its destination and was never heard from again. No search was undertaken, presumably because the VOC did not know whether or where the shipwrecked or if taken by pirates.

In the mid-20th century, Zuytdorp’s wreck site was identified on a remote part of the Western Australian coast between Kalbarri and Shark Bay, approximately 40 km north of the Murchison River. The name of the ship means “South Village”, after Zuiddorpe, an extant village in the South of Zeeland in the Netherlands, near the Belgian border.

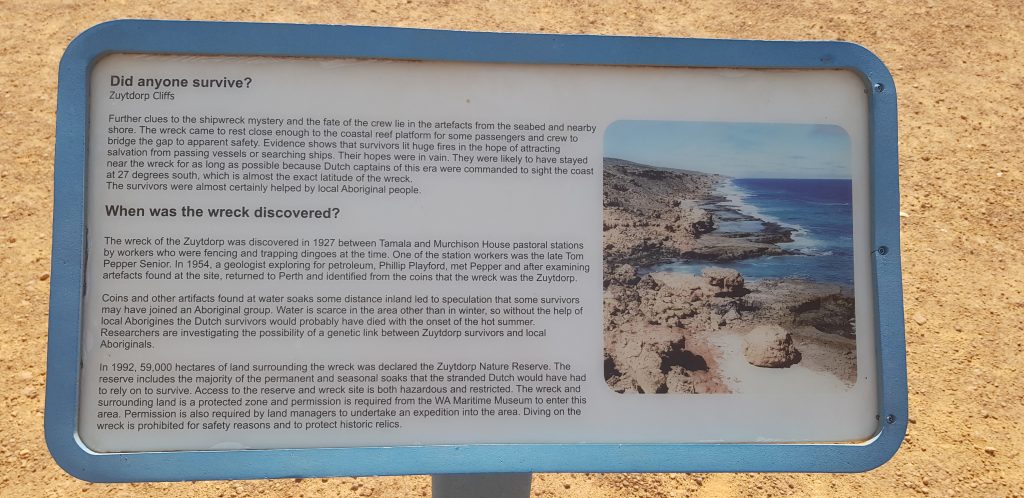

News of an unidentified shipwreck on the shore surfaced in 1834 when Aborigines told a farmer near Perth about a wreck – the colonists presumed it was a recent wreck and sent rescue parties who failed to find the wreck or any survivors. In 1927, wreckage was seen by an Indigenous-European family group from a clifftop near the border of Murchison house and Tamala Stations. Tamala Station head stockman reported the find to the authorities, with their first visit to the site occurring in 1941.

In 1954 Pepper gave Phillip Playford directions to the wreckage. Playford identified the relics as from Zuytdorp.The rugged section of coastline where the ship was wrecked was subsequently named the Zuytdorp Cliffs. In the 1980s investigations by the Western Australian Museum initially concentrated on recovering the silver deposits but was soon turned into a multi-disciplinary archaeological and cultural project.

We visited the site in 2018, when the pictures below were taken.

The Zeewijk – 1727

The Zeewijk was a new ship of the Zeeland Chamber of the VOC, her maiden voyage was from Vlissingen (Netherlands) to Batavia departing in November 1726 with 208 seamen and soldiers aboard, as well as a cargo of general building supplies and 315,836 guilders in 10 chests. Jan Steyns from Middelburg was the skipper.

In darkness at 7:30 p.m. on 9 June 1727 the ship crashed heavily into Half Moon Reef on the western edge of the Pelsaert Group of the Houtman Abrolhos island group. Survivors reached what would be later known as Gun Island. Much of the cargo was rescued as well.

In October the crew started to construct a vessel to carry them to Batavia; the Sloepie. Utilising materials from the wreck (including two swivel mounted cannon to protect the treasure from pirates) and local mangrove timber she became a 20 m (66 ft) long by 6 m (20 ft) wide sloop, resembling a North Sea fishing vessel. Launched on 28 February 1728, the Sloepie was the first ever European ship built in Australia. On 26 March, 88 men set off on the one-month journey to Batavia. Six died on the way, leaving 82 of the initial 208 to arrive in Batavia on 30 April 1728.

In 1840 HMS Beagle found relics at the camp site, including a VOC cannon and two coins dated 1707 and 1720 which helped to confirm that the site belonged to the Zeewijk. They named the Zeewyk Channel after the wreck. Much more artefacts were found of the following century.

Waaksamheijd – 1790

This story starts with the famous First Fleet of eleven vessels sailing into Sydney Cove in 1788. The plan was to establish a colony that would become self-sufficient. They brought with them supplies for 2 years for the 1000 people. After they had unloaded their supplies over a period of several months one by one, however, the First Fleet ships sailed away, leaving the two naval vessels, the Sirius and the Supply, to serve and protect the colony.

The tiny Supply was starting to wear out. It had been put to sea again in mid-February 1788 to carry a party of officers and convicts to Norfolk Island to start a settlement. Now it was sailing so low in the water that waves were washing over its decks. It would soon be of very little use.

In Sydney, the soil was not very productive for European agriculture and whatever grew was rapidly eaten by the local wildlife. Cattle had escaped and with them the availability of meat disappeared.

In September 1789 the storeship, the Guardian, left London for Sydney – heavily loaded with supplies. Unknown to Governor Phillip, the ship ran into an iceberg in the Southern Ocean. For a year people kept watching out for the ship to arrive in Sydney.

In April 1790, the Supply returned to Sydney with the devastating news that the Sirius had been wrecked on the reef at Norfolk Island. Supplies became so low that Governor Phillip could wait no longer, people were wearing rags, and many had no shoes, food was half-rationed.

Their only hope for longer term survival lay with the little brig, the Supply, now leaky and worn out. Supply was to make a run for the closest town, Batavia. Captain Henry Lidgbird Ball was authorised, while picking up supplies to charter a Dutch vessel to deliver more stores for Sydney. Fortunately the Waaksamheyd (Waakzaamheid, Waaksamheyd, Waakzamkeit) – a Dutch 300 ton mercantile vessel – would soon arrive in Batavia and the authorities ensured Ball that he would made this ship available for the rescue mission. was .

The Supply struggled back to Sydney on 18 October, carrying a precious cargo of food. In Batavia, a terrible fever had been raging and several of the Supply’s officers had died there. The good news was that the Waaksamheyd, was due in a few weeks, carrying 171 barrels of beef, 172 barrels of pork, seventy thousand pounds (that’s almost 32 tonnes) of rice, one thousand pounds (that’s 454 kilos) of sugar and 39 barrels of flour – all bought in Batavia.

Captain Deter Smit of the Waaksamheijd arrived at Port Jackson on 17 December 1790 and was warmly welcomed, ensuring that the fledgling colony survived.

On the way back, Captain John Hunter of the Sirius was transported back to England in 1792 on board the Waaksamheijd and faced a court martial over the loss of HMS Sirius. The ship left Port Jackson on 27 March 1791 with 125 men on board. She sailed via Batavia and then onto Mindanao. While seeking provisions on Mindanao, the shore party was attacked by natives, without any loss. They finally arrived at Portsmouth on 8 April 1792.

Willam Bradley wrote a journal: Voyage to NSW on the Dutch VOC ship Waaksamheijd.

Sydney Cove by William Bradley

Paul Budde (2021) with thanks to Wikipedia

Collection of maps of the early Dutch explorers can be found in the DACC Dutch Maritime History Archives

See also: